Image credit: Loco_2

Google has proposed a new protocol for downloading web pages called SPDY and CloudFlare will shortly be making it available in beta form. SPDY is designed to make web browsing faster without replacing HTTP. This blog post explains how it works and why it helps.

Current web browsing makes use of the HTTP protocol running over TCP.The TCP protocol underlies many other uses of the Internet (such assending and receiving email) because it provides reliable delivery ofdata. HTTP is independent of TCP and provides a mechanism for a webbrowser to ask for pages, graphics and other files needed to display aweb page.

SPDY sits between HTTP and TCP to speed up the HTTP protocol by changing how it interacts with TCP. First, let's look at getting a web page with HTTP over TCP without SPDY and then see how that changes with SPDY.

A typical web browsing session goes something like this: you type cloudflare.com into your browser and it sends an HTTP request over TCP to the cloudflare.com server asking for the the HTML of the page. The page is delivered and the browser sets about parsing the page to determine what else it needs to download (e.g. the style sheets and images that make up the page).

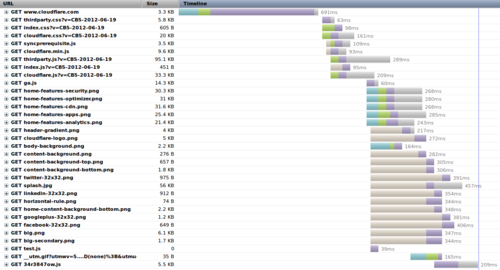

Here's a screen shot from Firebug running in Mozilla Firefox. You can see the page being downloaded at the top and then the parts of the page (such as JavaScript, CSS and images) being downloaded in parallel.

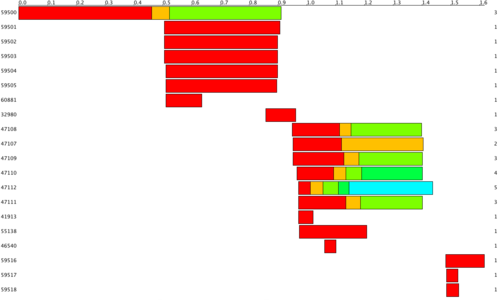

But what's not clear from that view is how Firefox is actually connecting to the web server and retrieving the parts of the page. For that it's necessary to dig a little deeper. Using a combination of Wireshark and a custom program written in Processing here's a view of the TCP connections and downloading of each part of the CloudFlare home page.

The scale at the top shows elapsed time in seconds. Down the left hand side is the identifier of each TCP connection; each row in the diagram is a single TCP connection. On the right hand side is a number indicating how many separate parts of the page (images, CSS, JavaScript) were downloaded by the connection on that row.

The colors just indicate different parts of the page being downloaded. The size of the bars equates to the total time to get that part of the page.

The first connection begins by downloading the HTML of the page and then straight after that Firefox reuses the connection and opens another 6 connections to retrieve parts of the page. By opening multiple connections Firefox gets to download in parallel, by reusing a connection Firefox saves time starting a connection.

After the first set of connections there are another set used to download parts of the page. Some of these connections are reused multiple times.

It's likely pretty obvious why Firefox uses multiple simultaneous connections (because downloading can happen in parallel), but its reuse of connections is a little less obvious. Connections are reused because of two costs: connection set up time and TCP slow start.

First, it takes time to set up a TCP connection. The browser connects to the server and goes through a handshake to establish the connection. In the example above each connection was taking roughly 50ms to establish. If you did that for all 36 items being downloaded it would add up to 1.8s (longer than the entire download took). So, clearly reusing a connection helps.

Image credit: Charles & Clint

But TCP slow start also matters. In a previous post I looked at the effect of bandwidth and latency on downloading. What that post didn't mention is that the theoretical download speed is only reached after a period of slowness at the beginning of a TCP connection.

To avoid causing congestion on the Internet, every TCP connection starts slowly and works up to the maximum speed available. This is called TCP Slow Start. So, each time a new TCP connection is established there's a double penalty: connection set up time and slow start. TCP slow start is also problematic on high latency links because detecting the maximum speed available on the connection requires back-and-forth packet exchanges.

Thus, to make efficient use of TCP the ideal browser would open a small number of connections and reuse them. That way the connection cost would be low, TCP slow start would be minimized and download speed would be maximized.

So, why did Firefox open 20 separate connections and only reuse them for a small number of requests each? Take a look at the line corresponding to connection 47108 in the diagram. Notice how a small download (in blue) had to wait behind a large download (in red).

Since the web browser can't predict how large or small the response to each request will be it is not able to order requests for efficient delivery. So, there's a balancing act to find the right number of connections to minimize page load time as bandwidth, latency, connection time and slow start have to be taken into account.

Using a small number of connections would result in blocking (a long slow download of say a large image could block a small quicker download because there's no 'overtaking' in HTTP); a large number of connections would avoid blocking and pay the price of connection set up and slow start.

Also, opening a large number of connections would place a load on the web server as each connection takes up resources on the server itself.

These problems come about in part because HTTP is synchronous: a request is made for part of a page and the connection it was made on needs to wait for the response. A better protocol would allow multiple requests to be sent and the responses returned in the order they are available. Line 47108 would look very different in that case: all three requests could be sent and the small one would be returned first even though it was the second request.

Image credit: Capt' Gorgeous

SPDY fixes all these problems in one go.

SPDY allows a single connection to be used for multiple requests. The requests can be sent in any order and responses come back in the order that they are available. Since a single connection is used the connection set up cost and slow start are minimized. Since requests can be answered in any order there's no blocking.

Of course, SPDY also does other things (such as compression of previously uncompressed parts of HTTP), but its core benefit is that it decouples HTTP from TCP and in doing so allows asynchronous, overlapping HTTP requests on a single connection. All without changing HTTP at all.

And shortly CloudFlare will be rolling out SPDY to our customers. Information about the beta is here.