Today, we’re excited to announce our solution for arguably the biggest issue affecting Accelerated Mobile Pages (AMP): the inability to use real origin URLs when serving AMP-cached content. To allow AMP caches to serve content under its origin URL, we implemented HTTP signed exchanges, which extend authenticity and integrity to content cached and served on behalf of a publisher. This logic lives on Cloudflare Workers, meaning that adding HTTP signed exchanges to your content is just a simple Workers application away. Publishers on Cloudflare can now take advantage of AMP performance and have AMP caches serve content with their origin URLs. We're thrilled to use Workers as a core component of this solution.

HTTP signed exchanges are a crucial component of the emerging Web Packaging standard, a set of protocols used to package websites for distribution through optimized delivery systems like Google AMP. This announcement comes just in time for Chrome Dev Summit 2018, where our colleague Rustam Lalkaka spoke about our efforts to advance the Web Packaging standard.

What is Web Packaging and Why Does it Matter?

You may already see the need for Web Packaging on a daily basis. On your smartphone, perhaps you’ve searched for Christmas greens, visited 1-800-Flowers directly from Google, and have been surprised to see content served under the URL https://google.com/amp/1800flowers.com/blog/flower-facts/types-of-christmas-greens/amp. This is an instance of AMP in action, where Google serves cached content so your desired web page loads faster.

Visiting 1-800 Flowers through AMP without HTTP signed exchange

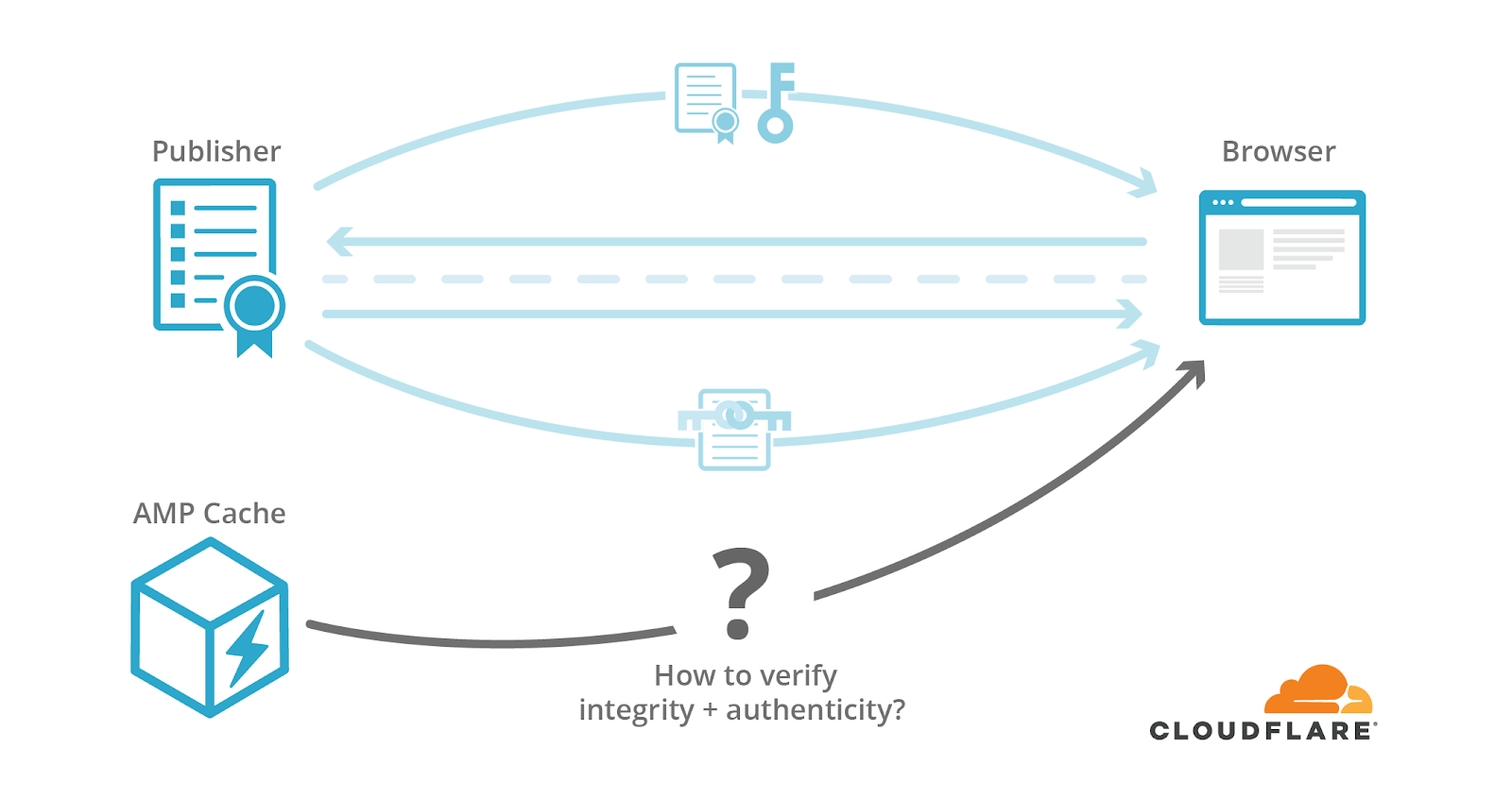

Google cannot serve cached content under publisher URLs for clear security reasons. To securely present content from a URL, a TLS certificate for its domain is required. Google cannot provide 1-800-Flowers’ certificate on the vendor’s behalf, because it does not have the corresponding private key. Additionally, Google cannot, and should not be able to, sign content using the private key that corresponds to 1-800-Flowers’ certificate.

The inability to use original content URLs with AMP posed some serious issues. First, the google.com/amp URL prefix can strip URLs of their meaning. To the frustration of publishers, their content is no longer directly attributed to them by a URL (let alone a certificate). The publisher can no longer prove the integrity and authenticity of content served on their behalf.

Second, for web browsers the lack of a publisher’s URL can call the integrity and authenticity of a cached webpage into question. Namely, there’s no clear way to prove that this response is a cached version of an actual page published by 1-800-Flowers. Additionally, cookies are managed by third-party providers like Google instead of the publisher.

Enter Web Packaging, a collection of specifications for “packaging” website content with information like certificates and their validity. The HTTP signed exchanges specification allows third-party caches to cache and service HTTPS requests with proof of integrity and authenticity.

HTTP Signed Exchanges: Extending Trust with Cryptography

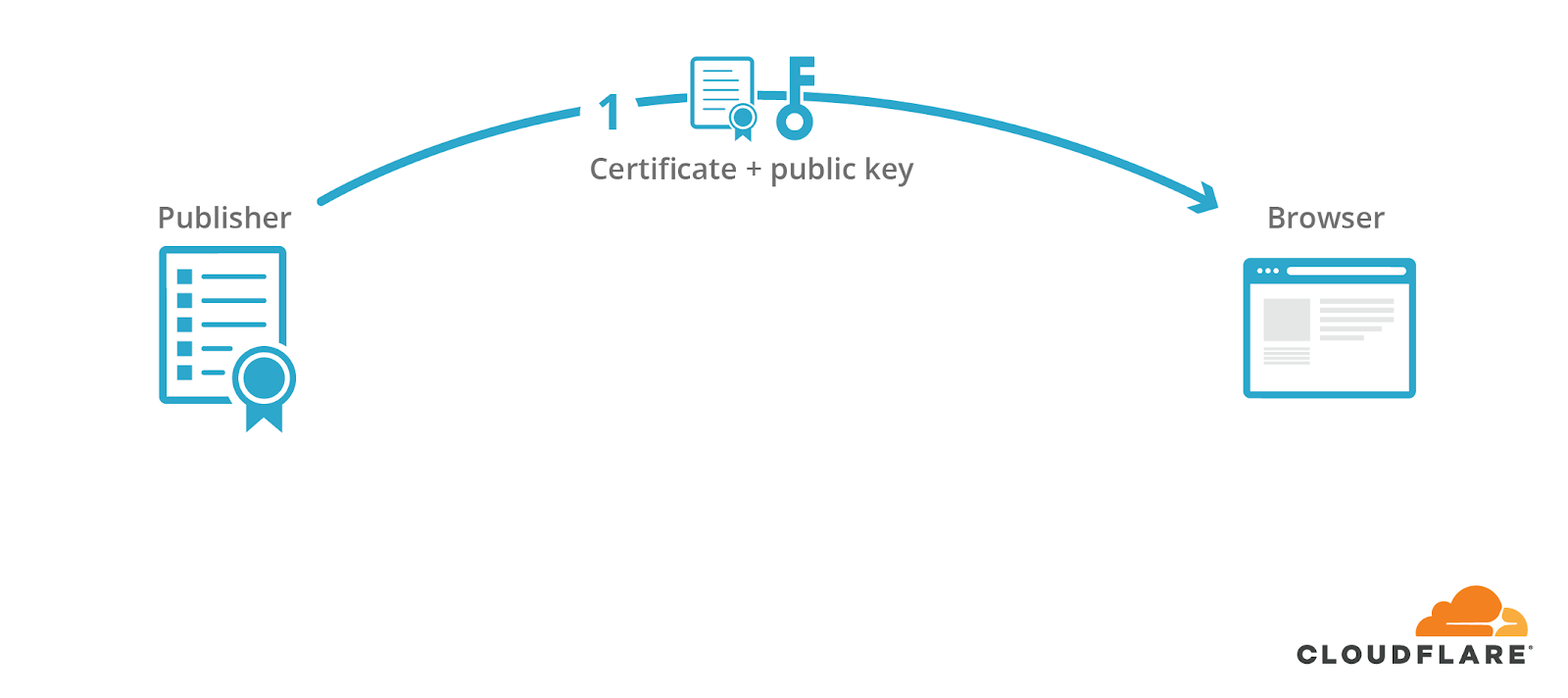

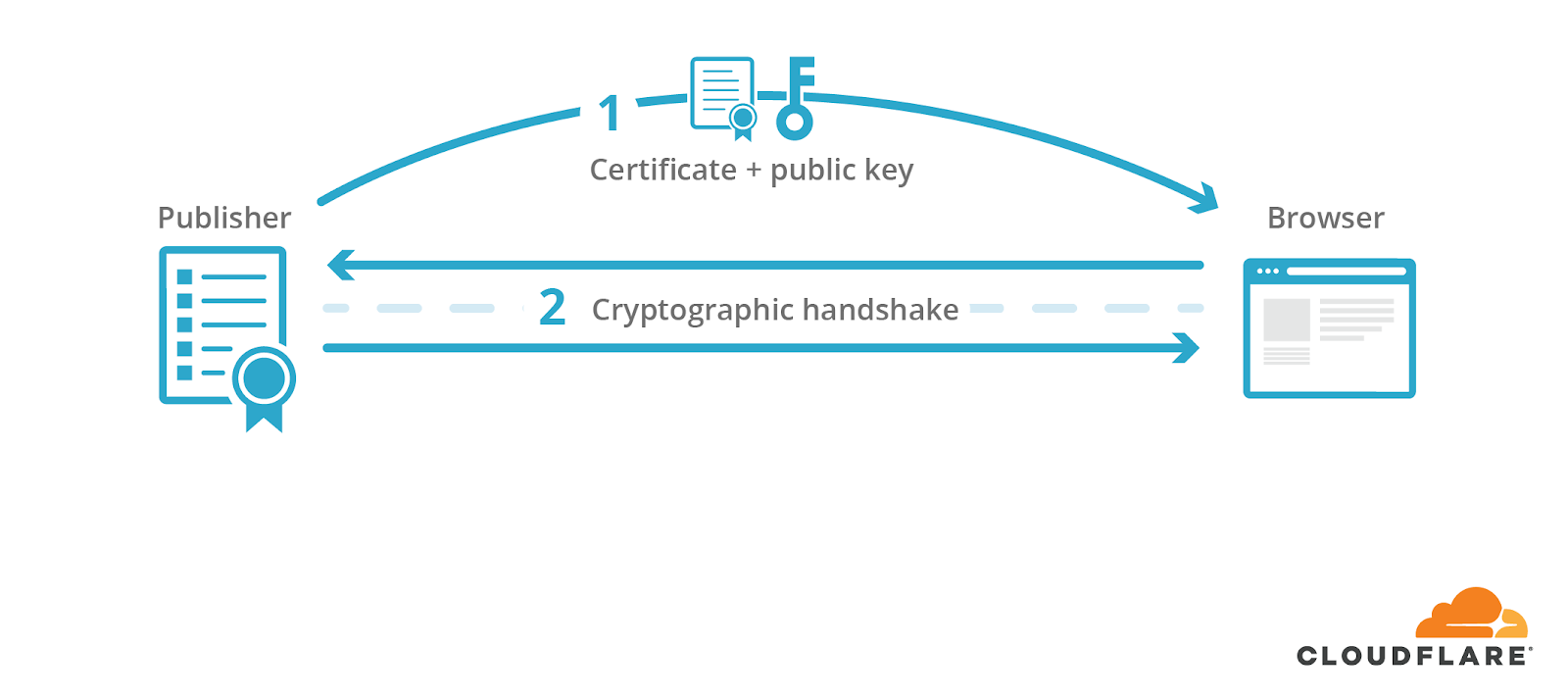

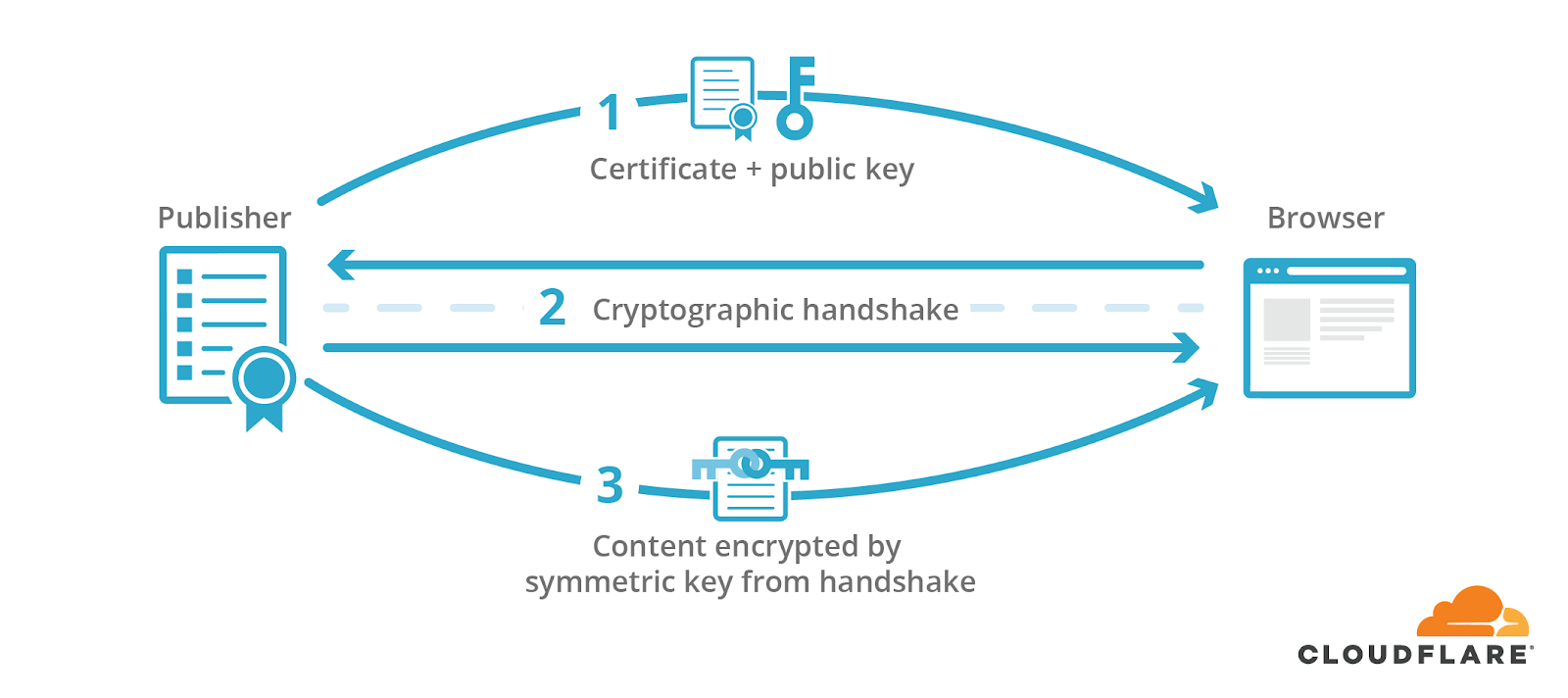

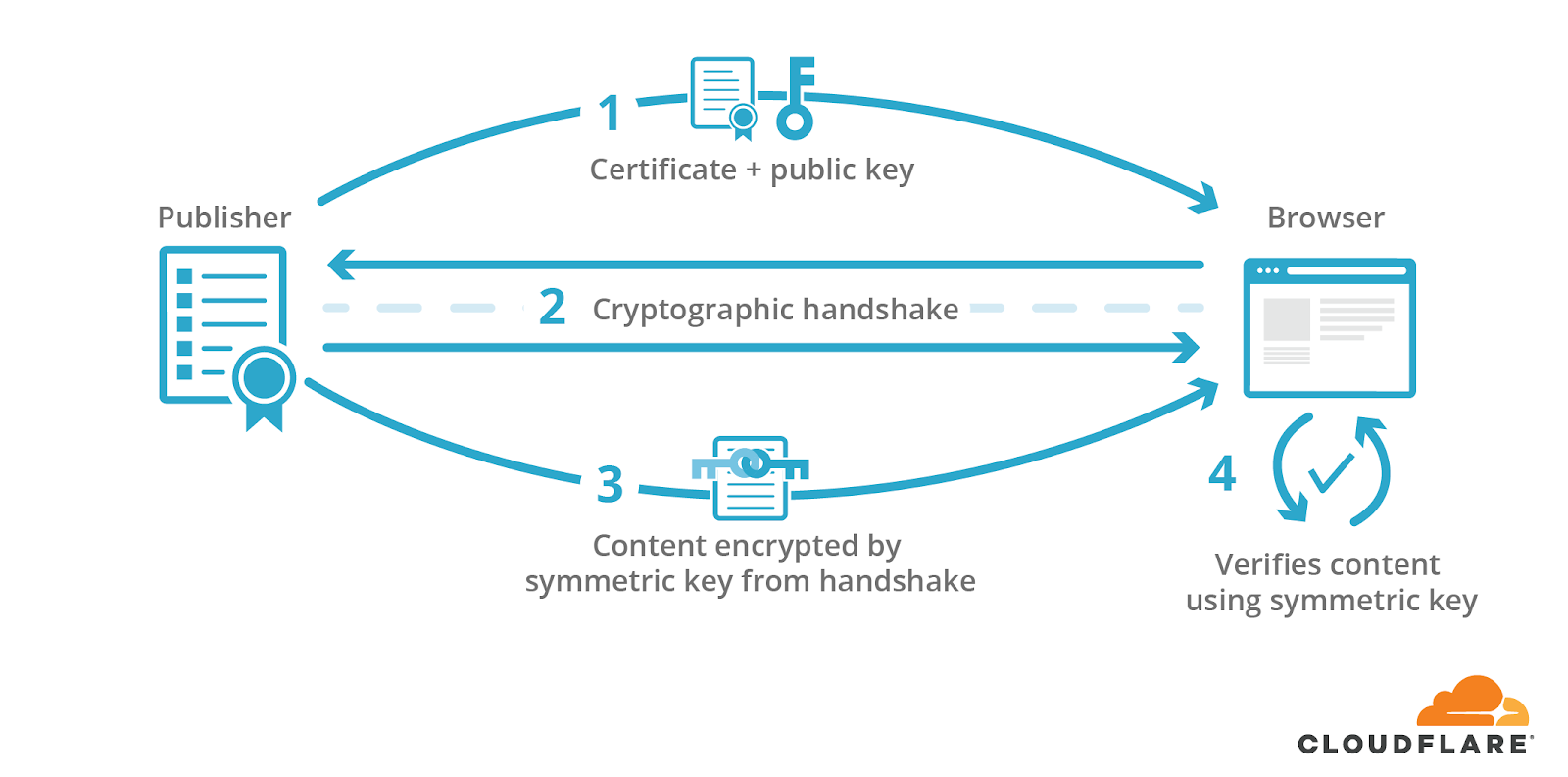

In the pre-AMP days, people expected to find a webpage’s content at one definitive URL. The publisher, who owns the domain of the definitive URL, would present a visitor with a certificate that corresponds to this domain and contains a public key.

The publisher would use the corresponding private key to sign a cryptographic handshake, which is used to derive shared symmetric keys that are used to encrypt the content and protect its integrity.

The visitor would then receive content encrypted and signed by the shared key.

The visitor’s browser then uses the shared key to verify the response’s signature and, in turn, the authenticity and integrity of the content received.

With services like AMP, however, online content may correspond to more than one URL. This introduces a problem: while only one domain actually corresponds to the webpage’s publisher, multiple domains can be responsible for serving a webpage. If a publisher allows AMP services to cache and serve their webpages, they must be able to sign their content even when AMP caches serve it for them. Only then can AMP-cached content prove its legitimacy.

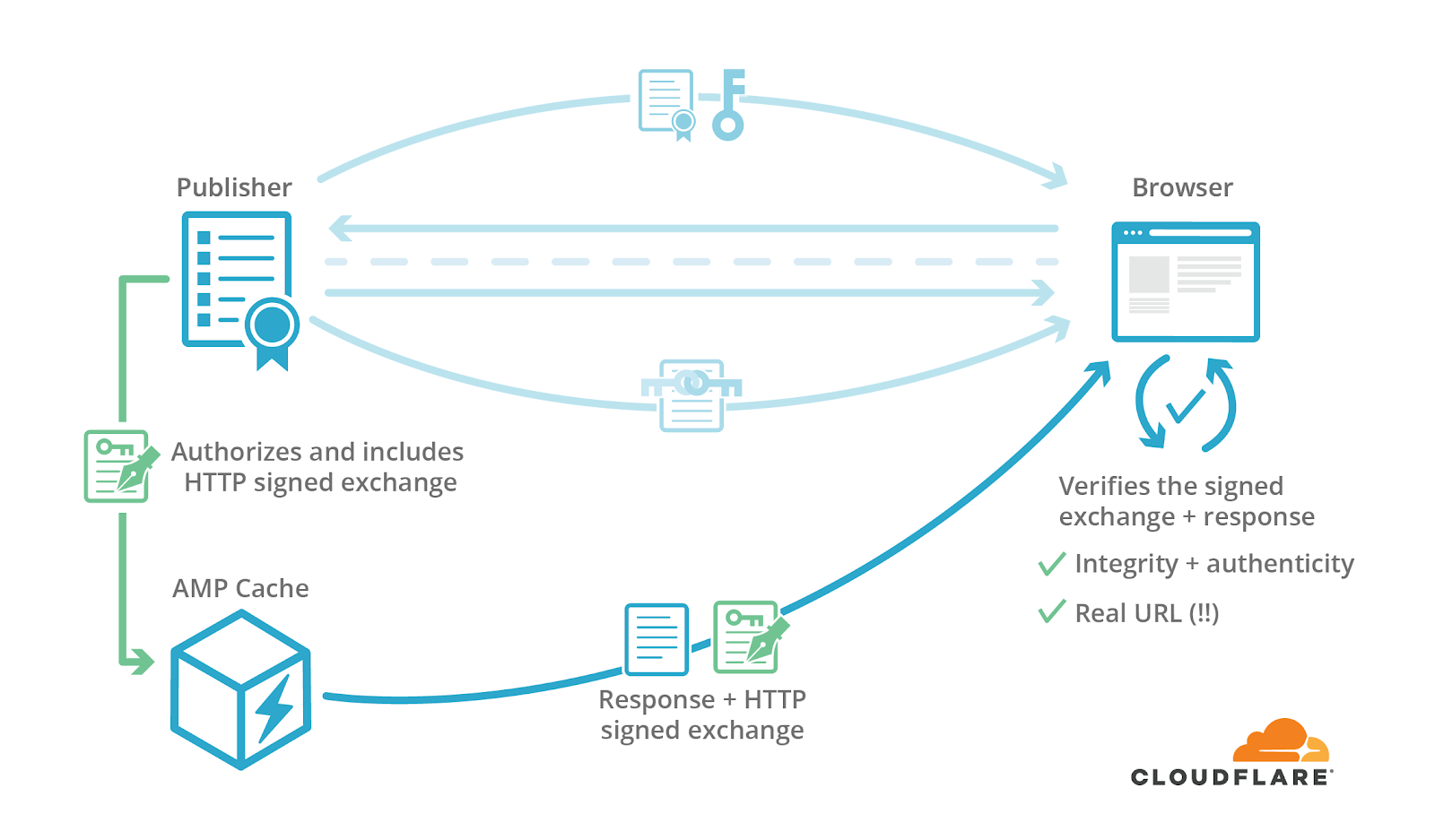

HTTP signed exchanges directly address the problem of extending publisher signatures to services like AMP. This IETF draft specifies how publishers may sign an HTTP request/response pair (an exchange). With a signed exchange, the publisher can assure the integrity and authenticity of a response to a specific request even before the client makes the request. Given a signed exchange, the publisher authorizes intermediates (like Google’s AMP Cache) to forward the exchanges; the intermediate responds to a given request with the corresponding response in the signed HTTP request/response pair. A browser can then verify the exchange signature to assert the intermediate response’s integrity and authenticity.

This is like handing out an answer key to a quiz signed by the instructor. Having a signed answer sheet is just as good as getting the answer from the teacher in real time.

The Technical Details

An HTTP signed exchange is generated by the following steps.First, the publisher uses MICE (Merkle Integrity Content Encoding) to provide a concise proof of integrity for the response included in the exchange. To start, the response is split into blocks of some record size bits long. Take, for example, a message ABCD, which is divided into record-size blocks A, B, C, and D. The first step to constructing a proof of integrity is to take the last block, D, and compute the following:

proof(D) = SHA-256(D || 0x0)This produces proof(D). Then, all consequent proof values for blocks are computed as follows:

proof(C) = SHA-256(C || proof(D) || 0x1)

proof(B) = SHA-256(B || proof(C) || 0x1)

proof(A) = SHA-256(A || proof(B) || 0x1)The generation of these proofs build the following tree:

proof(A)

/\

/ \

/ \

A proof(B)

/\

/ \

/ \

B proof(C)

/\

/ \

/ \

C proof(D)

|

|

DAs such, proof(A) is a 256-bit digest that a person who receives the real response should be able to recompute for themselves. If a recipient can recompute a tree head value identical to proof(A), they can verify the integrity of the response they received. In fact, this digest plays a similar role to the tree head of a Merkle Tree, which is recomputed and compared to the presented tree head to verify the membership of a particular node. The MICE-generated digest is stored in the Digest header of the response.

Next, the publisher serializes the headers and payloads of a request/response pair into CBOR (Concise Binary Object Representation). CBOR’s key-value storage is structurally similar to JSON, but creates smaller message sizes.

Finally, the publisher signs the CBOR-encoded request/response pair using the private key associated with the publisher’s certificate. This becomes the value of the sig parameter in the HTTP signed exchange.

The final HTTP signed exchange appears like the following:

sig=*MEUCIQDXlI2gN3RNBlgFiuRNFpZXcDIaUpX6HIEwcZEc0cZYLAIga9DsVOMM+g5YpwEBdGW3sS+bvnmAJJiSMwhuBdqp5UY=*;

integrity="digest/mi-sha256";

validity-url="https://example.com/resource.validity.1511128380";

cert-url="https://example.com/oldcerts";

cert-sha256=*W7uB969dFW3Mb5ZefPS9Tq5ZbH5iSmOILpjv2qEArmI=*;

date=1511128380; expires=1511733180Services like AMP can send signed exchanges by using a new HTTP response format that includes the signature above in addition to the original response.

When this signature is included in an AMP-cached response, a browser can verify the legitimacy of this response. First, the browser confirms that the certificate provided in cert-url corresponds to the request’s domain and is still valid. It next uses the certificate’s public key, as well as the headers and body values of request/response pair, to check the authenticity of the signature, sig. The browser then checks the integrity of the response using the given integrity algorithm, digest/mi-sha256 (aka MICE), and the contents of the Digest header. Now the browser can confirm that a response provided by a third party has the integrity and authenticity of the content’s original publisher.

After all this behind-the-scenes work, the browser can now present the original URL of the content instead of one prefixed by google.com/amp. Yippee to solving one of AMP’s most substantial pain points!

Generating HTTP Signed Exchanges with Workers

From the overview above, the process of generating an HTTP signed exchange is clearly involved. What if there were a way to automate the generation of HTTP signed exchanges and have services like AMP automatically pick them up? With Cloudflare Workers… we found a way you could have your HTTP origin exchange cake and eat it too!

We have already implemented HTTP signed exchanges for one of our customers, 1-800-Flowers. Code deployed in a Cloudflare Worker is responsible for fetching and generating information necessary to create this HTTP signed exchange.

This Worker works with Google AMP’s automatic caching. When Google’s search crawler crawls a site, it will ask for a signed exchange from the same URL if it initially responds with Vary: AMP-Cache-Transform. Our HTTP signed exchange Worker checks if we can generate a signed exchange and if the current document is valid AMP. If it is, that Vary header is returned. After Google’s crawler sees this Vary header in the response, it will send another request with the following two headers:

AMP-Cache-Transform: google

Accept: application/signed-exchange;v=b2When our implementation sees these header values, it will attempt to generate and return an HTTP response with Content-Type: application/signed-exchange;v=b2.

Now that Google has cached this page with the signed exchange produced by our Worker, the requested page will appear with the publisher’s URL instead of Google’s AMP Cache URL. Success!

If you’d like to see HTTP signed exchanges in action on 1-800-Flowers, follow these steps:

Install/open Chrome Beta for Android. (It should be version 71+).

Go to goo.gl/webpackagedemo.

Search for “Christmas greens.”

Click on the 1-800-Flowers link -- it should be about 3 spots down with the AMP icon next to it. Along the way to getting there you should see a blue box that says "Results with the AMP icon use web packaging technology." If you see a different message, double check that you are using the correct Chrome Beta.An example of AMP in action for 1-800-Flowers:

Visiting 1-800 Flowers through AMP with HTTP signed exchange

The Future: Deploying HTTP Signed Exchanges as a Worker App

Phew. There’s clearly a lot of infrastructure for publishers to build for distributing AMP content. Thankfully Cloudflare has one of the largest networks in the world, and we now have the ability to execute JavaScript at the edge with Cloudflare Workers. We have developed a prototype Worker that generates these exchanges, on the fly, for any domain. If you’d like to start experimenting with signed exchanges, we’d love to talk!

Soon, we will release this as a Cloudflare Worker application to our AMP customers. We’re excited to bring a better AMP experience to internet users and advance the Web Packaging standard. Stay tuned!

The Big Picture

Web Packaging is not simply a technology that helps fix the URL for AMP pages, it’s a fundamental shift in the way that publishing works online. For the entire history of the web up until this point, publishers have relied on transport layer security (TLS) to ensure that the content that they send to readers is authentic. TLS is great for protecting communication from attackers but it does not provide any public verifiability. This means that if a website serves a specific piece of content to a specific user, that user has no way of proving that to the outside world. This is problematic when it comes to efforts to archive the web.

Services like the Internet Archive crawl websites and keep a copy of what the website returns, but who’s to say they haven’t modified it? And who’s to say that the site didn’t serve a different version of the site to the crawler than it did to a set of readers? Web Packaging fixes this issue by allowing sites to digitally sign the actual content, not just the cryptographic keys used to transport data. This subtle change enables a profoundly new ability that we never knew we needed: the ability to record and archive content on the Internet in a trustworthy way. This ability is something that is lacking in the field of online publishing. If Web Packaging takes off as a general technology, it could be the first step in creating a trusted digital record for future generations to look back on.

Excited about the future of Web Packaging and AMP? Check out Cloudflare Ampersand to see how we're implementing this future.