Continuing our commitment to high quality open-source software, we’re happy to announce release 1.2 of CFSSL, our TLS/PKI Swiss Army knife. We haven’t written much about CFSSL here since we originally open sourced the project in 2014, so we thought we’d provide an update. In the last 20 months, we have added a ton of great features, and CFSSL has attracted an active community of users and contributors. Users range from large SaaS providers (Heroku) to game companies (Riot Games) and the newest Certificate Authority (Let’s Encrypt). For them and for CloudFlare, CFSSL has become a core tool for automating certificates and TLS configurations. With added support for configuration scanning, automated provisioning via the transport package, revocation, certificate transparency and PKCS#11, CFSSL is now even more powerful.

We’re also happy to announce CFSSL’s new home: cfssl.org. From there you can try out CFSSL’s user interface, download binaries, and test some of its features.

Motivation

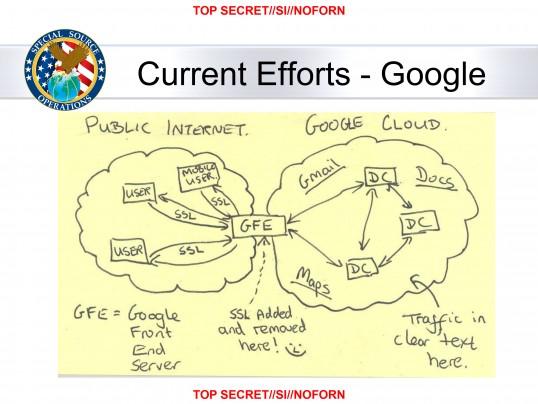

This 2013 National Security Agency (NSA) slide describing how data from Google’s internal network was collected by intelligence agencies was eye-opening—and shocking—to many technology companies. The idea that an attacker could read messages passed between services wasn’t technically groundbreaking, but it did reveal a security flaw in the way many distributed systems were designed. Many companies only encrypted the data to the border of their datacenter, not inside. The slide showed that private physical networks are being subverted to extract data passing through them. And just because a network has a security perimeter, it doesn’t mean that data can be safely sent between applications unencrypted inside that perimeter. In short: treat your own network as hostile.

This mentality helped shape CloudFlare’s philosophy for securing internal services and resulted in a simple rule:

Services should only communicate with each other using encrypted and mutually authenticated protocols.

With this in mind we started tackling the harder problem of how to manage the encryption keys for these services. To tackle the issue of service-to-service encryption, we built our own public key infrastructure using CFSSL. Much of the new features we’re introducing in this post came about from our effort to make this system robust.

We have also made an effort to use standards-compliant and interoperable technology. By incorporating support for certificate transparency, OSCP, and CRL, the standards used by the public Internet can now be used in your private infrastructure. Now, on to the new features.

Scan

CFSSL now has a full-featured TLS endpoint scanner.

Just because a server uses encryption, it doesn’t mean that it is secure. There have been a series of vulnerabilities in TLS that only affect some configurations. To keep your server and its visitors protected against the nearly monthly new attacks you need to pick the right configuration. Staying secure requires testing your configuration against the latest vulnerabilities, and keeping your configuration updated against new threats.

History of vulnerabilities in SSL/TLS

The gold standard for testing a website’s TLS configuration is Ivan Ristić’s SSL Labs. It provides a simple letter grade for your site’s configuration (sites using CloudFlare get an A, by the way, and A+ if you enable HSTS). The drawback of SSL Labs is that it only works on public websites: you can’t use it for internal services. At CloudFlare, we needed an easy way to check the configuration of our services as well as our customers’ origins (which are typically not publicly accessible).

To solve this, CloudFlare added functionality to CFSSL to scan a TLS endpoint to evaluate how securely it’s configured. With it, we are able to check the configuration of internal services and protected customer origins for the following configuration issues:

IPv4/IPv6 connectivity

Certificate validity (expiration, trust chain, hostnames, etc.)

Supported cipher suites and algorithms

Session resumption

Revoked certificates

Each scan provides a grade of "Good" or "Bad". CFSSL Scan can also be used to scan entire IP ranges or lists of hosts. It can be used either as a CLI or as API-driven server.

Using the CLI is a simple command:

$ cfssl scan cloudflare.com

{

"Connectivity": {

"DNSLookup": {

"grade": "Good",

"output": [

"198.41.215.162",

"198.41.214.162",

"2400:cb00:2048:1::c629:d6a2",

"2400:cb00:2048:1::c629:d7a2"

]

},

"TCPDial": {

"grade": "Good"

},

"TLSDial": {

"grade": "Good"

}

},

"PKI": {

"ChainExpiration": {

"grade": "Good",

"output": "2016-11-30T23:59:59Z"

},

"ChainValidation": {

"grade": "Warning",

"output": [

"Certificate for COMODO ECC Extended Validation Secure Server CA is valid for too long"

]

},

"MultipleCerts": {

"grade": "Good"

}

},

"TLSHandshake": {

"CertsByCiphers": {

"grade": "Good",

"output": {

"TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_3DES_EDE_CBC_SHA": "SHA256WithRSA",

"TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA": "SHA256WithRSA",

"TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA256": "SHA256WithRSA",

"TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_AES_128_GCM_SHA256": "SHA256WithRSA",

"TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_AES_256_CBC_SHA": "SHA256WithRSA",

"TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_AES_256_CBC_SHA384": "SHA256WithRSA",

"TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_AES_256_GCM_SHA384": "SHA256WithRSA",

"TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_CHACHA20_POLY1305_SHA256": "SHA256WithRSA",

"TLS_RSA_WITH_3DES_EDE_CBC_SHA": "SHA256WithRSA",

"TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA": "SHA256WithRSA",

"TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA256": "SHA256WithRSA",

"TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_GCM_SHA256": "SHA256WithRSA",

"TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_256_CBC_SHA": "SHA256WithRSA",

"TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_256_CBC_SHA256": "SHA256WithRSA",

"TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_256_GCM_SHA384": "SHA256WithRSA"

}

}

}

}CFSSL Scan also accessible as part of the new CFSSL UI.

Transport Package

An important design pattern in security engineering is secure defaults. Developers want to write secure software and aren’t always security experts, let alone crypto gurus. The two trickiest parts of deploying an application that speaks TLS are:

Configuration

Key management

Simplicity is the key to empowering developers to use encryption in their services. We created the CFSSL Transport package to make these two tasks easy for our Go developers.

Transport is a Go library that takes regular HTTP or TCP connections, and transparently turns them into encrypted connections. Transport handles all the sticky points so that the developer doesn’t have to. This includes creating a private key, getting a certificate for it using a CFSSL CA, renewing certificates before they expire, and choosing the correct cryptographic parameters. If you’re writing a service in Go, you no longer need to know how PKI works.

Certificate Issuance with CFSSL CA

Not only does the Transport handle setting up and rotating certificates, it automatically checks to make sure the services your service are connecting to are using a valid certificate, including checking for revocation (more on that later).

OCSP Check with CFSSL CA

Internal CAs can be used to set up coarse-grained authorization between services. For example, if you have both an API server and a database, you can set up a dedicated CA for each of them. In the example below, the API server CA is in orange and the DB CA is in red. You can then configure the DB to only trust connections from the API server and vice versa. This type of setup can provide a baseline level of authorization enforcement for your applications. The transport package lets you automate the setup of these mutually-authenticated connections. This type of setup is covered in a previous blog post.

Once you have a CFSSL CA (or a multi-root CA) up and running, it just takes a few lines of code to start using TLS in your Go application. Just swap your standard net.Dial or net.Listen/Accept with transport.Dial and transport.Listen/Accept.

Before:

conn, err := net.Dial("tcp", addr)

if err != nil {

// handle error

}After (configuration file location stored in the conf variable):

var id = new(core.Identity)

data, err := ioutil.ReadFile(conf)

if err != nil {

// handle error

}

err = json.Unmarshal(data, id)

if err != nil {

// handle error

}

// Renew 5 minutes before expiry

tr, err := transport.New(5 * time.Minute, id)

if err != nil {

// handle error

}

conn, err := transport.Dial(addr, tr)

if err != nil {

// handle error

}You can start playing around with the transport package with some examples from Github:

https://github.com/cloudflare/cfssl/tree/master/transport/example

Revocation and PostgreSQL support

CC Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

One of the nice things about CFSSL is that you can easily spin it up inside your infrastructure and have a certificate authority. One of the risks of running a PKI is infrastructure compromise. If the private key material for a certificate falls into the wrong hands, there need to be mechanisms so that the rest of the system knows to no longer trust that certificate.

The first step in knowing which certificates are trusted is knowing which certificates have been issued. To solve this, we added the ability to keep track, in a persistent database, of which certificates have been issued and the subset of those that have been revoked. We are big fans of PostgreSQL, so we built a database backend for CFSSL in PostgreSQL, but other backends like MySQL are in development. You can now set up CFSSL to use a certificate database with very little work, and we leveraged that integration to create an automated revocation system.

The two standard mechanisms for signaling that a certificate is no longer trusted are certificate revocation lists (CRLs) and the online certificate status protocol (OCSP). CFSSL now fully supports both of these mechanisms.

A CRL is simply a list of revoked certificate serial numbers. It covers all certificates issued by a CA that have not expired, and is digitally signed by the CA’s private key. When a client obtains a certificate, it can simply look at this list to check to see if the certificate has been revoked. CRL files can grow quite a bit if a lot of certificates are revoked, and can therefore cause some scalability issues. We saw this after Heartbleed, when we revoked a large number of customer certificates at once.

Partly to combat these scalability issues, OCSP was introduced. OCSP provides on-demand answers about the revocation status of a given certificate. An OCSP responder is a service that returns signed answers to the question "is this certificate revoked?". The response is either "Yes" or "No". Each response is signed by the CA and has a validity period so the client knows how long to cache the response.

CFSSL now has an OCSP responder service that can be configured to run in a distributed way, without access to the CA. There are also OCSP management tools in CFSSL to automatically populate the data for the OCSP responder and keep it fresh using the certificate database.

In CFSSL, you can now programmatically create CRLs and OCSP responses for certificates issued by your CA. Using standards-compatible revocation mechanisms allows these certificates to be shared outside of our infrastructure and to work with most software that implements TLS.

Certificate Transparency

Another exciting new PKI standard is Certificate Transparency (CT). It helps provide (as the name implies) transparency into the workings of a certificate authority by providing an append-only log of issued certificates.

You can think of CT as a public ledger of all certificates issued. Any certificate on the list (even if issued for use on a private network) is made public and can be checked to see if it was issued according to the rules of the CA/Browser forum. If you encounter a certificate that is not on the ledger, then it may have been created fraudulently. Google Chrome currently requires all Extended Validation certificates used by websites to be in the CT log.

CFSSL now allows you to submit certificates to a CT log at issuance time and automatically embed the proof that it has been logged into the certificate. Running a CT log inside your internal infrastructure is a nice way to audit your CA and catch mis-issuances.

PKCS #11

CFSSL is great for software deployments, as you can spin it up anywhere and run it on any platform that Go supports. You can even use our convenient Dockerfiles to deploy it in a containerized environment. However, in some situations (like running a publicly-trusted CA), keeping a private key in software is not secure enough. For these situations, hardware-based protection is needed.

The industry standard protocol for working with cryptographic hardware is called PKCS#11. With help from Richard Barnes of Mozilla and others we were able to add support for PKCS#11 into CFSSL. This feature is can be enabled in programs that use the signer/local package and the pkcs11key package. We also have plans to add command line support using the PKCS#11 URI specification. If you have a PKCS#11 interface to your HSM, certificate creation using that key is fully supported by the cfssl/signer package. Power users including Let’s Encrypt use CFSSL to run their publicly trusted CA while keeping the private key in a FIPS 140-2 certified HSM.

Conclusion

Open source is hard. Different people have different needs, and as a project maintainer you have to be respectful of these needs while honoring the spirit of the project. CloudFlare’s needs for CFSSL are not identical to the needs of its other users. We have attempted to strike a balance between building a tool for our own specific use cases and building a great general-purpose toolkit for PKI/TLS. We are grateful to the open source community for their valuable contributions to this project and are proud to be part of the tradition of free and open source software.

I’d like to thank one of the largest contributors to CFSSL over the last year: the Let’s Encrypt project. They have contributed code reviews and useful features while integrating CFSSL into Boulder, the software that manages their certificate authority. I’d also like to thank the Open Academy participants from Cornell and UCSD who worked on the project for a semester, and everyone else who helped contribute to this release. The core CFSSL team is Kyle Isom, Zi Lin, Jacob Haven, and Nick Sullivan.