Today we’re proud to introduce CFSSL—our open source toolkit for everything TLS/SSL. CFSSL is used internally by CloudFlare for bundling TLS/SSL certificates chains, and for our internal Certificate Authority infrastructure. We use this tool for all our TLS certificates.

Creating a certificate bundle is a common pain point for website operators, and doing it right is important for website security AND speed (CloudFlare does both). Getting the correct bundle together is a black art, and can quickly become a debugging nightmare if it's not done correctly. We wrote CFSSL to make bundling easier. By picking the right chain of certificates, CFSSL solves the balancing act between performance, security, and compatibility.

Staying true to our promise to make the web fast and safe, we’re open sourcing CFSSL. We believe CFSSL will be useful for anyone building a site using HTTPS—from website owners to large software-as-a-service companies. CFSSL is written in Go and available on the CloudFlare Github account. It can be used as a web service with a JSON API, and as a handy command line tool.

CFSSL is the result of real-world expertise about how the TLS ecosystem on the Web works that you can gain by working at CloudFlare’s scale. These are hard-won lessons, applied in code. The rest of this blog post serves as an under-the-hood look at how and why CFSSL works, and how you can use it as a certificate bundler or as a lightweight CA.

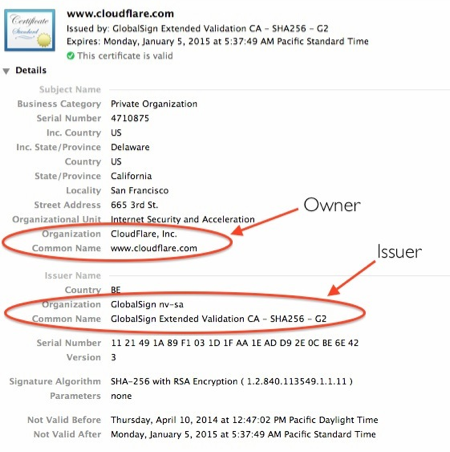

As you can see in the above image, the key is owned by CloudFlare, Inc., and the issuer is GlobalSign (a well-known CA). GlobalSign has issued a certificate named “GlobalSign Extended Validation CA - SHA256 - G2”; this G2 certificate is signed by another certificate called “GlobalSign Root CA - R2”. Note that the root certificate does not have an issuer—it is signed by its own private key. In other words, the root vouches for itself.

The reason your browser trusts a root certificate is because browsers have a list of root certificates that they implicitly trust, and when a site is trusted it will show the lock icon to the left of the web address (see image below). Certain certificates are on the list typically because they have been around for some time, and they belong to certificate authorities that have gone through a rigorous security audit. GlobalSign is one of these trusted authorities; therefore, its root certificate is in the list of trusted root certificates for nearly every browser.

What Are SSL Certificates?

SSL certificates form the core of trust on the web by assuring the identity of websites. This trust is built by digitally binding a cryptographic key to an organization’s identity. An SSL certificate will bind domain names to server names, and company names to locations. This ensures that if you go to your bank’s web site, for example, you know for sure it is your bank, and you are not giving out your information to a phishing scam.

A certificate is a file that contains a public key which is bound to a record of its owner. The mechanism that makes this binding trustworthy is called the Public Key Infrastructure and public-key cryptography is the glue that makes this possible.

A certificate is associated with a private key that corresponds to the certificate's public key, which is stored separately. The certificate comes with a digital signature from a trusted third-party called a certificate authority or CA. Let's examine the cloudflare.com certificate.

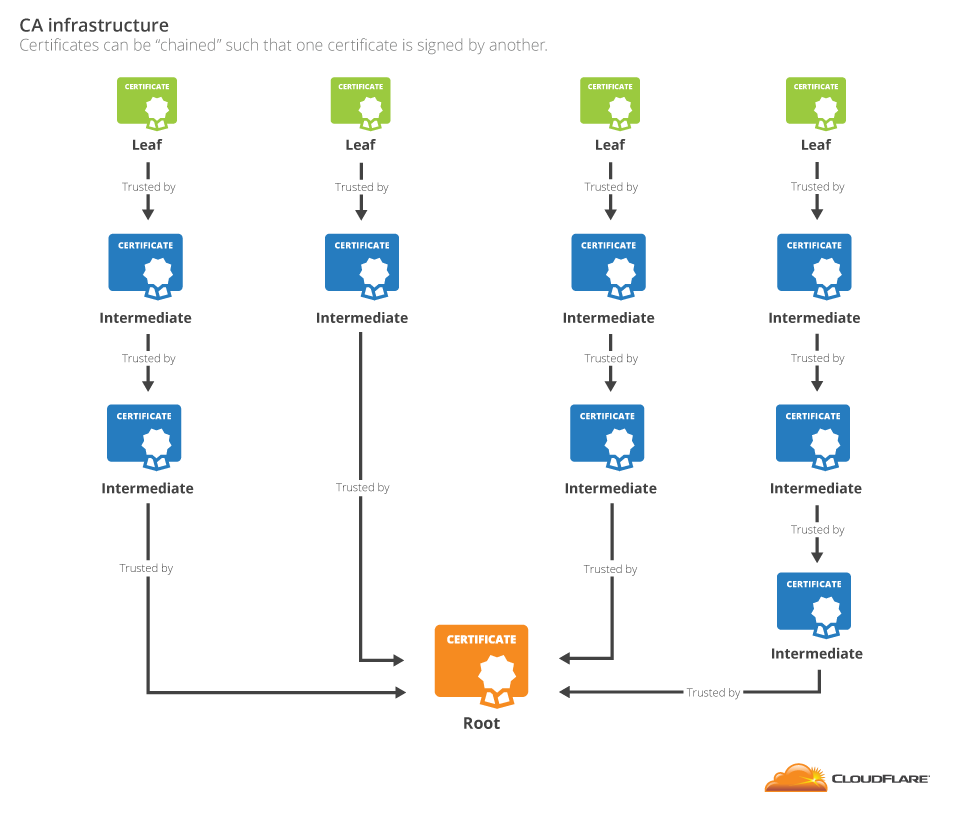

The length of intermediate certificates in a chain can vary, but chains will always have one leaf and one root.

Unfortunately, there is a catch for the owner of the leaf certificate: presenting only the leaf certificate to the browser is usually not enough. The intermediate certificates are not always known to the browser, requiring the website to include them with the leaf certificate. The list of certificates that the browser needs to validate a certificate is called a certificate bundle. It should contain all the certificates in the chain up to the first certificate known to the browser. In the case of the CloudFlare website, this bundle contains both the cloudflare.com certificate and the GlobalSign G2 intermediate.

CFSSL was written to make certificate bundling easier.

How CFSSL Makes Certificate Bundling Easier

If you are running a website (or perhaps some other TLS-based service) and need to install a certificate, CFSSL can create the certificate bundle for you. Start with the following command:

$ cfssl bundle -cert mycert.crt

This will output a JSON blob containing the chain of certificates along with relevant information extracted from that chain. Alternatively, you can run the CFSSL service that responds to requests with a JSON API:

$ cfssl serve

This command opens up an HTTP service on localhost that accepts requests. To bundle using this API, send a POST request to this service, [http://localhost:8888/api/v1/cfssl/bundle](http://localhost:8888/api/v1/cfssl/bundle), using a JSON request such as:

{ "certificate": }

CloudFlare’s SSL service will return a JSON response of the form:

{ "result": {}, "success": true, "errors": [], "messages": [], }

(Developers take note: this response format is a preview of our upcoming CloudFlare API rewrite; with this API, we can use CFSSL as a service for certificate bundling and more—stay tuned.)

If you upload your certificate to CloudFlare, this is what is used to create a certificate bundle for your website.

To create a certificate bundle with CFSSL, you need to know which certificates are trusted by the browsers you hope to display content to. In a controlled corporate environment, this is usually easy since every browser is set up with the same configuration; however, it becomes more difficult when creating a bundle for the web.

Different Certs for Different Folks

Each browser has unique capabilities and configurations, and a certificate bundle that’s trusted in one browser might not be trusted in another; this can happen for several reasons:

Different browsers trust different root certificates.Some browsers trust more root certificates than others. For example, the NSS root store used in Firefox trusts 143 certificates; however, Windows 8.1 trusts 391 certificates. So a bundle with a chain that expects the browser to trust a certificate exclusive to the Windows root store will appear as untrusted in Firefox.

Older systems might have old root stores.Some browsers run on older systems that have not been updated to trust recently-created certificate authorities. For example, Android 2.2 and earlier don't trust the “GoDaddy Root Certificate Authority G2” because that root certificate was created after they were released.

Older systems don't support modern cryptography.Users on Windows XP SP2 and earlier can't validate certificates signed by certain intermediates. This includes the “DigiCert SHA2 High Assurance Server CA” because the hash function SHA-2 used in this certificate was standardised after Windows XP was released.

In order to provide maximum compatibility between SSL chains and browsers, you often have to pick a different certificate chain than the one originally provided to you by your CA. This alternate chain might contain a different set of intermediates that are signed by a different root certificate. Alternate chains can be troublesome. They tend to contain a longer list of certificates than the default chain from the CA, and longer chains cause site connections to be slower. This lag is because the web server needs to send more certificates (i.e. more data) to the browser, and the browser has to spend time verifying more certificates on its end. Picking the right chain can be tricky.

CFSSL helps pick the right certificate chain, selecting for performance, security, and compatibility.

How to Pick the Best Chain

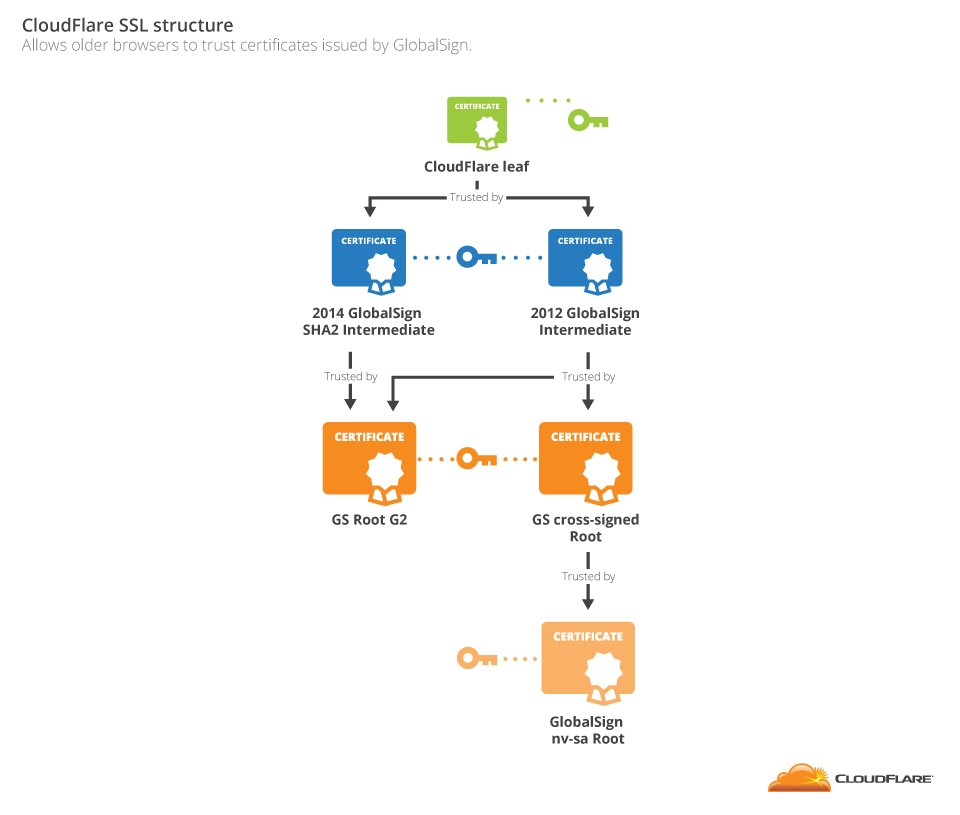

The chain of trust works by following the keys used to sign certificates, and there can be multiple chains of trust for the same keys.

In this diagram, all of the intermediates have the same public key and represent the same identity (GlobalSign's intermediate signing certificate), and they are signed by the GlobalSign root key; however, the issuance date for each chain and signature type are different.

For some outdated browsers, the current GlobalSign root certificate is not trusted, so GlobalSign used an older CA (GlobalSign nv-sa) to sign their root certificate. This allows older browsers to trust certificates issued by GlobalSign.

Each of these are valid chains for some browsers, but each has drawbacks:

CloudFlare leaf → GlobalSign SHA2 Intermediate.This chain is trusted by any browser that trusts the GS root G2 and supports SHA2 (i.e., this chain would not be trusted by a browser on Windows XP SP2).

CloudFlare leaf → 2012 GlobalSign Intermediate → GS Root G2.This chain is trusted by any browser that trusts GS Root G2, but does not benefit from the stronger cryptographic properties of the SHA-2 hashing algorithm.

CloudFlare leaf → 2012 GlobalSign Intermediate → GS cross-signed root.This chain is trusted by any browser that trusts the GlobalSign nv-sa root, but uses the older (and weaker) GlobalSign nv-sa root certificate.

This last chain is the most common because it’s trusted by more browsers; however, it’s also the longest, and has weaker cryptography.

CFSSL can create either the most common or the optimal bundle, and if you need help deciding, the documentation that ships with CFSSL has tips on choosing.

If you decide to create the optimal bundle, there’s a chance it might not work in some browsers; however, CFSSL is configured to let you know specifically which browsers it will not work with. For example, it will warn the user about bundles that contains certificates signed with advanced hash functions such as SHA2; they can be problematic for certain operating systems like Windows XP SP2.

CFSSL at CloudFlare

All paid CloudFlare accounts receive HTTPS service automatically; to make this happen, our engineers do a lot of work behind scenes.

CloudFlare must obtain a certificate for each site on the service, and we want these certificates to be valid on as many browsers as possible; getting a certificate that works in multiple browsers is a challenge, but CFSSL makes things easier.

To start, a key-pair is created for the customer through a call to CFSSL's genkey API with the required certificate information:

{ "CN": "customer.com", "hosts": [ "customer.com", "www.customer.com" ], "key": { "algo": "rsa", "size": 2048 }, "names": [ { "C": "US", "L": "San Francisco", "O": "Customer", "OU": "Website", "ST": "California" } ] }

Next, the CFSSL service responds with a key and a Certificate Signature Request (CSR). The CSR is sent to the CA to verify a site’s identity. Once the CA has validated the CSR, and the identity of the site, they then return a certificate signed by one of their issuing intermediates.

Once we have a certificate for a site (whether created by our CA partner or uploaded by the customer), we send the certificate to CFSSL's bundler to create a certificate bundle for the customer.

By default, we pick the most common chain. For customers who prefer performance to compatibility, we’ll soon introduce an option to rebundle certificates for optimum chains.

CFSSL as a Certificate Authority

CFSSL is not only a tool for bundling a certificate, it can also be used as a CA. This is possible because it covers the basic features of certificate creation including creating a private key, building a certificate signature request, and signing certificates.

You can create a brand new CA with CFSSL using the -initca option. As we saw above, this takes a JSON blob with the certificate request, and creates a new CA key and certificate:

$ cfssl gencert -initca ca_csr.json

This will return a CA certificate and CA key that is valid for signing. The CA is meant to function as an internal tool for creating certificates. CFSSL should be used behind a middle layer that processes incoming requests, and ensures they conform to policy; we use it behind the CloudFlare site as an internal service.

Here’s an example of signing a certificate with CFSSL on the command line:

$ cfssl sign -ca-key=test-key.pem -ca=test-cert.pem www.example.com example.csr

Alternatively, a POST request containing the CSR and hostname can be sent to the CFSSL service via the /api/v1/cfssl/sign endpoint. To run the service call the serve command as follows:

$ cfssl serve -address=localhost -port=8888 -ca-key=test-key.pem -ca=test-cert.pem

If you already have a CFSSL instance running (in this case on localhost, but it can be anywhere), you can automate certificate creation with the gencert command’s -remote option. For example, if CFSSL is running on localhost, running the following gives you a private key and a certificate signed by the CA:

$ cfssl gencert -remote="localhost:8888" www.example.com csr.json

At CloudFlare we use CFSSL heavily for Railgun and other internal services. Special thanks go to Kyle Isom, Zi Lin, Sebastien Pahl, and Dane Knecht, and the rest of the CloudFlare team for making this release possible.

Looking Ahead

CloudFlare’s mission is to help build a better web, and we believe that improved certificate bundling and certificate authority tools are a step in the right direction. Encrypted sites create a safer, more private internet for everyone; by open-sourcing CFSSL, we’re making this process easier.

We have big plans for the CA part of this tool. Currently, we run CFSSL on secure locked-down machines, but plan to add stronger hardware security. Adding stronger hardware security involves integrating CFSSL with low-cost Trusted Platform Modules (TPMs). This ensures that private keys stay private, even in the event of a breach.

For additional information on CFSSL and our other open source projects, check out our Github page. We encourage users to file issues on Github as they find bugs.