Last November, we rolled out HTTP/2 support for all our customers. At the time, HTTP/2 was not in wide use, but more than 88k of the Alexa 2 million websites are now HTTP/2-enabled. Today, more than 70% of sites that use HTTP/2 are served via CloudFlare.

CC BY 2.0 image by Roger Price

Incremental Improvements On SPDY

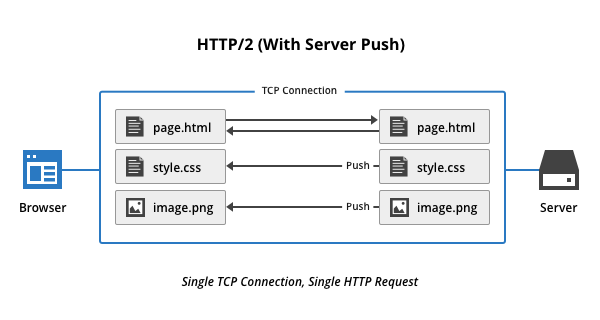

HTTP/2’s main benefit is multiplexing, which allows multiple HTTP requests to share a single TCP connection. This has a huge impact on performance compared to HTTP/1.1, but it’s nothing new—SPDY has been multiplexing TCP connections since at least 2012.

Some of the most important aspects of HTTP/2 have yet to be implemented by major web servers or edge networks. The real promise of HTTP/2 comes from brand new features like Header Compression and Server Push. Since February, we’ve been quietly testing and deploying HTTP/2 Header Compression, which resulted in an average 30% reduction in header size for all of our clients using HTTP/2. That's awesome. However, the real opportunity for a quantum leap in web performance comes from Server Push.

Pushing Ahead

Today, we’re happy to announce HTTP/2 Server Push support for all of our customers. Server Push enables websites and APIs to speculatively deliver content to the web browser before the browser sends a request for it. This behavior is opportunistic, since in some cases, the content might already be in the client’s cache or not required at all.

It’s been touted as one of the major features of HTTP/2, and by enabling it, we cover the entire set of HTTP/2 features for all of our users. You can see it in action on our live Server Push demo.

Server Push provides significant performance gains if used judiciously. In its most basic form, Server Push allows the server to “bundle” assets that the client didn’t ask for. It works by sending PUSH_PROMISE—a declaration of the intention to send the assets, followed by the actual assets.

Upon the receipt of a PUSH_PROMISE, the client may respond with a RST_STREAM message, indicating this asset is not needed. Even in this case, due to the asynchronous nature of HTTP/2, the client may receive the asset before the server gets the RST_STREAM message.

The PUSH_PROMISE looks a lot like an HTTP/2 GET request, and the client attempts to match received push promises before sending outgoing requests.

Enabling Server Push

All of our customers using HTTP/2 now have Server Push enabled, but unfortunately, Server Push isn’t one of those features that just works—you’ll need to do a little bit of work to truly leverage the benefits of Server Push.

Our implementation follows the guidelines laid out in the W3C’s draft standard on the use of a preload keyword in Link headers[1], and we will continue to track that standard as it evolves.

So, if you want to push assets for a given request, you simply add a specially formatted Link header to the response:

Link: </asset/to/push.js>; rel=preload; as=scriptThose links can be manually added, but they’re already created automatically by many publishing tools or via plugins for popular content management systems (CMS) such as WordPress.

Only relative links will be pushed by our edge servers, which means Server Push won’t work with third-party resources.

Disabling Server Push

The Link header was originally designed to let browsers know that they should preload an asset. If you still need this behavior for legacy reasons, you can append the nopush directive to the header, like so:

Link: </dont/want/to/push/this.css>; rel=preload; as=style; nopushIs Server Push For Me?

Server Push has the potential for tremendous performance gains. However, it’s not able to speed up every website, and it can even degrade the performance somewhat if you get overzealous. Generally, the downside of pushing assets that will end up unused is only the wasted bandwidth, while the upside is a speedup equivalent to one round trip from the client to our edge network.

Both the downside and the upside are mostly evident on slow, lossy connections, such as mobile networks. We suggest you profile the behavior of your individual website/API with and without Server Push to estimate the benefits. In our testing, we saw around a 45% performance gain when using Server Push on a mobile network.

Also note that because Server Push operates over a given HTTP/2 connection, it can only be used to push resources from your domain. If your website is bottlenecked on third-party assets, Server Push is unlikely to help you.

Some of the best use cases for HTTP/2 Server Push are:

Uncacheable content - Content that is not cached on the edge benefits from Server Push, since it will be requested from the origin earlier in the connection.

All assets on a requested page - By pushing all the CSS, JS, and image assets on a given page, it’s possible to transfer the entire page in a single round trip. This is only useful when no third party assets are blocking the page rendering. If the majority of the assets are cached on the client’s browser, this behavior can be wasteful.

The most likely next page - If there is a link on the loaded page that is most likely clicked next (for example the most recent post in a blog) you could push both the HTML and all of that pages assets. When the user clicks the link, it will render almost instantly.

Profiling Server Push

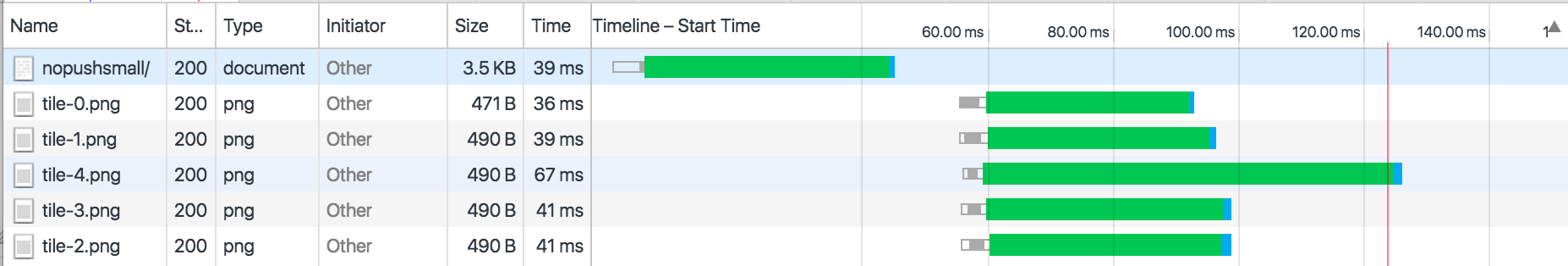

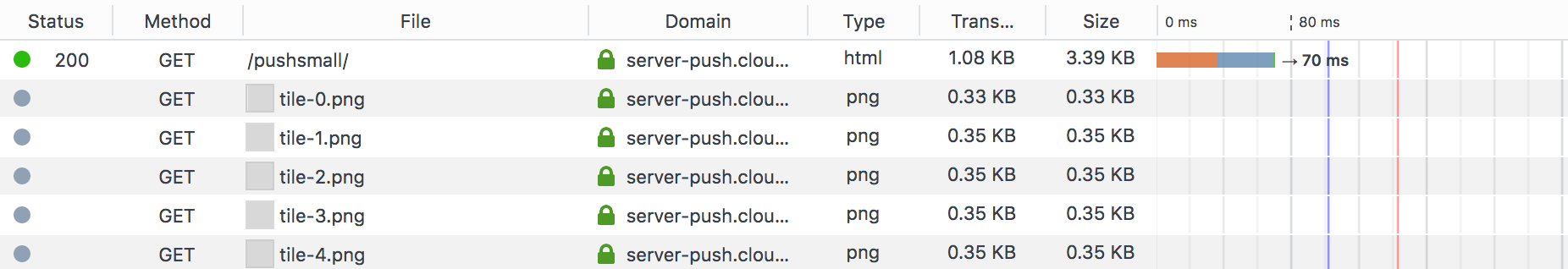

There are currently several tools and browsers that support Server Push. However, to visualize the performance benefits of the feature, the current Canary version of Google Chrome is the best. Here is an example of a webpage with five images loading with and without Server Push, as depicted in the timeline:

Plain HTTP/2:

After the main page is loaded (and some processing time) the browser makes a request for the five images. After another round trip, those images are delivered and loaded.

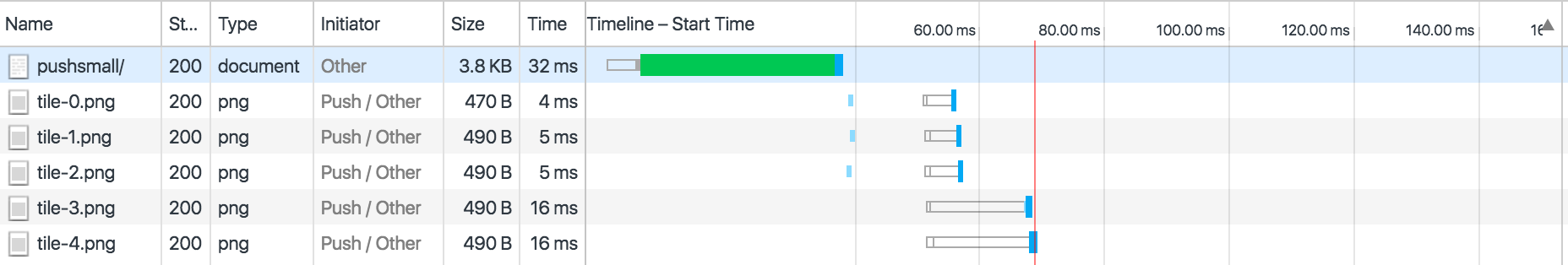

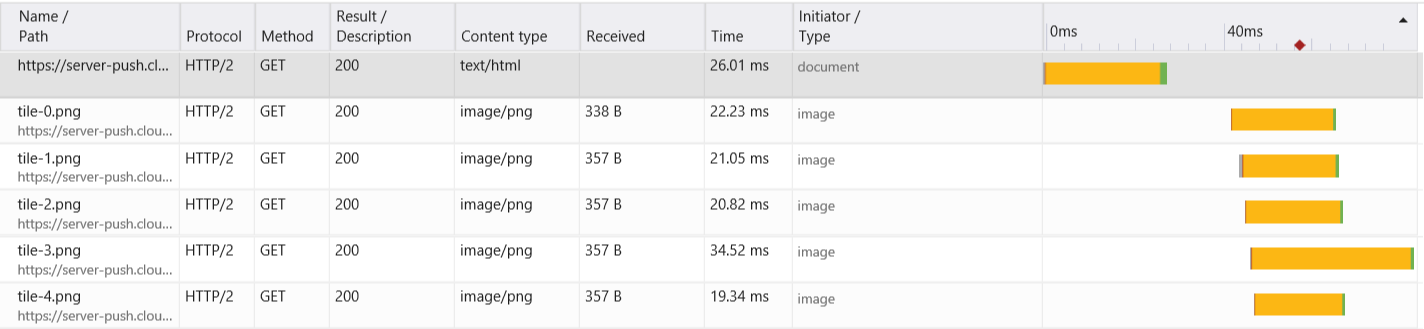

HTTP/2 + Server Push:

With Server Push enabled, we can see that the images are delivered while the page is being processed, thus no additional round trip is required. As soon as the images are needed, Chrome matches them with existing Push Promises and immediately uses them.

In Canary Chrome, you can also see that the pushed assets are identified in the Initiator column as Push/Other.

Other browsers:

Firefox

Pushed assets will not get a timeline and are identified by a solid grey circle (unlike cached content that is identified by a non-solid circle, and a “cached” indication in the “Transferred tab”).

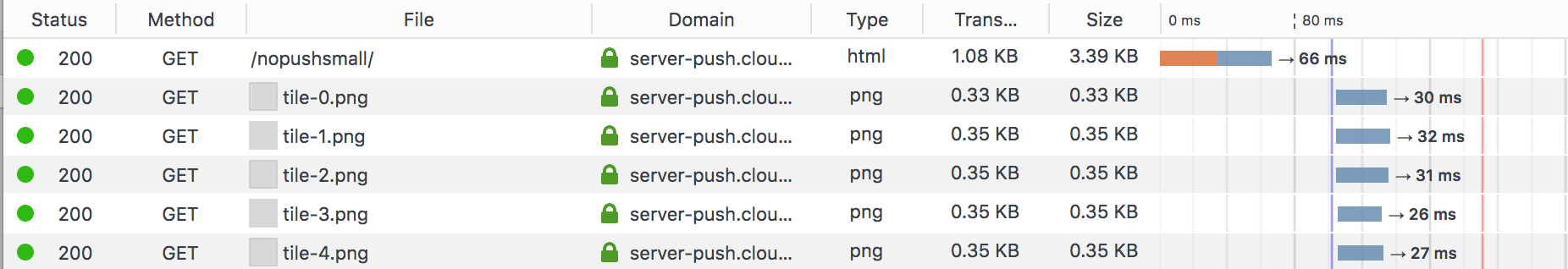

Plain HTTP/2:

HTTP/2 + Server Push:

Edge

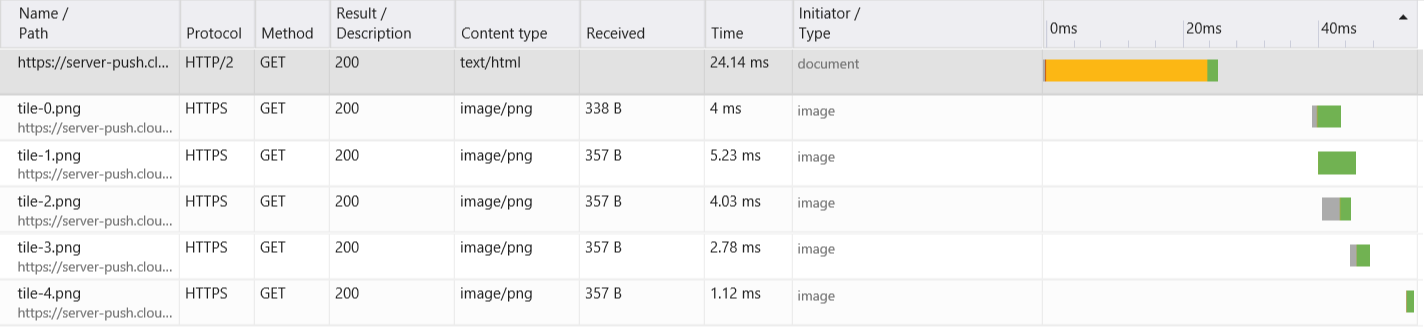

Pushed assets won’t have the yellow bar in the timeline (TTFB), and under the Protocol tab, the protocol will appear as HTTPS and not HTTP/2.

Plain HTTP/2:

HTTP/2 + Server Push:

Safari

The Safari browser does not support Server Push at the moment, but support is expected in the near future.

What’s Next For HTTP/2?

In the future, we plan to develop new tools to help our users to make more educated decisions in regards to Server Push. Over time, CloudFlare will even be able to predict the best assets to push automatically.

This feature is very new, and CloudFlare is the first major provider to deploy it at scale. We look forward to hearing from customers who make use of Server Push, now that we’ve made it available for experimentation.

We believe that Server Push is the most important upgrade to the web since SPDY. It has enormous potential to speed up the Internet since, for the first time, it gives website owners the power to send information to a web browser before the browser even asks for it.We’ll also be monitoring the still ongoing process of HTTP/2 development, especially efforts to make Server Push more aware of the client’s cache (thus reducing the number of redundant pushes).

We are currently only looking at link elements in HTTP headers and not in page HTML. ↩︎