This post is also available in 简体中文, 繁體中文, 日本語, Deutsch, Français, Español and Português.

The Internet, in its purest form, is a loosely connected graph of independent networks (also called Autonomous Systems (AS for short)). These networks use a signaling protocol called BGP (Border Gateway Protocol) to inform their neighbors (also known as peers) about the reachability of IP prefixes (a group of IP addresses) in and through their network. Part of this exchange contains useful metadata about the IP prefix that are used to inform network routing decisions. One example of the metadata is the full AS-path, which consists of the different autonomous systems an IP packet needs to pass through to reach its destination.

As we all want our packets to get to their destination as fast as possible, selecting the shortest AS-path for a given prefix is a good idea. This is where something called prepending comes into play.

Routing on the Internet, a primer

Let's briefly talk about how the Internet works at its most fundamental level, before we dive into some nitty-gritty details.

The Internet is, at its core, a massively interconnected network of thousands of networks. Each network owns two things that are critical:

1. An Autonomous System Number (ASN): a 32-bit integer that uniquely identifies a network. For example, one of the Cloudflare ASNs (we have multiple) is 13335.

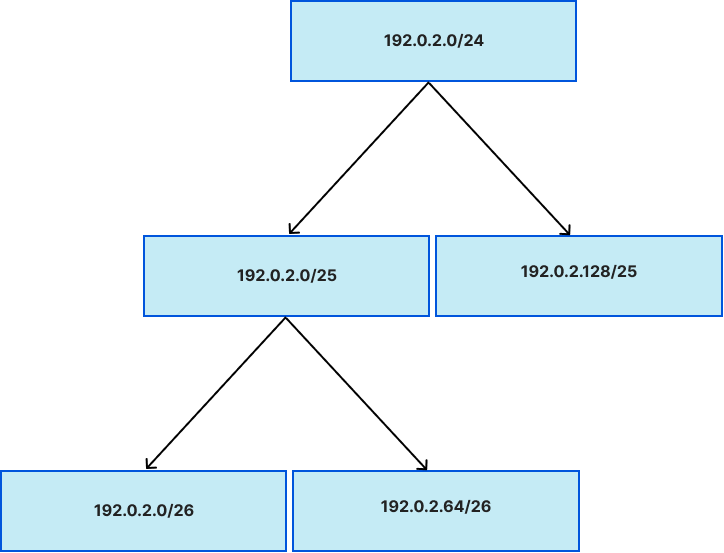

2. IP prefixes: An IP prefix is a range of IP addresses, bundled together in powers of two: In the IPv4 space, two addresses form a /31 prefix, four form a /30, and so on, all the way up to /0, which is shorthand for “all IPv4 prefixes''. The same applies for IPv6 but instead of aggregating 32 bits at most, you can aggregate up to 128 bits. The figure below shows this relationship between IP prefixes, in reverse -- a /24 contains two /25s that contains two /26s, and so on.

To communicate on the Internet, you must be able to reach your destination, and that’s where routing protocols come into play. They enable each node on the Internet to know where to send your message (and for the receiver to send a message back).

As mentioned earlier, these destinations are identified by IP addresses, and contiguous ranges of IP addresses are expressed as IP prefixes. We use IP prefixes for routing as an efficiency optimization: Keeping track of where to go for four billion (232) IP addresses in IPv4 would be incredibly complex, and require a lot of resources. Sticking to prefixes reduces that number down to about one million instead.

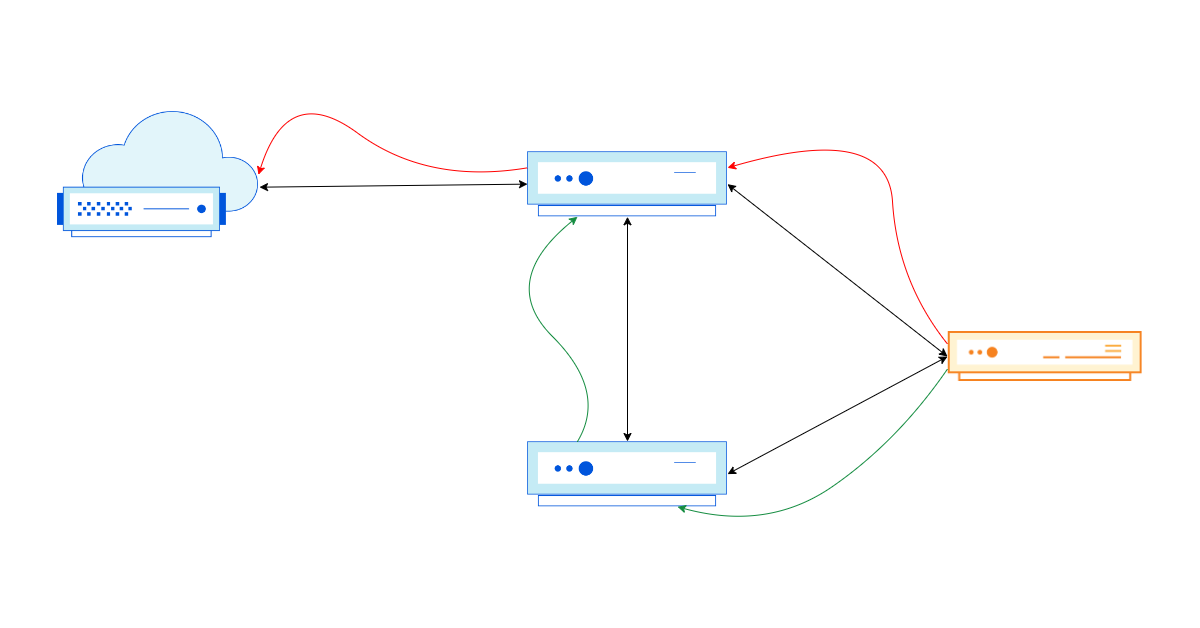

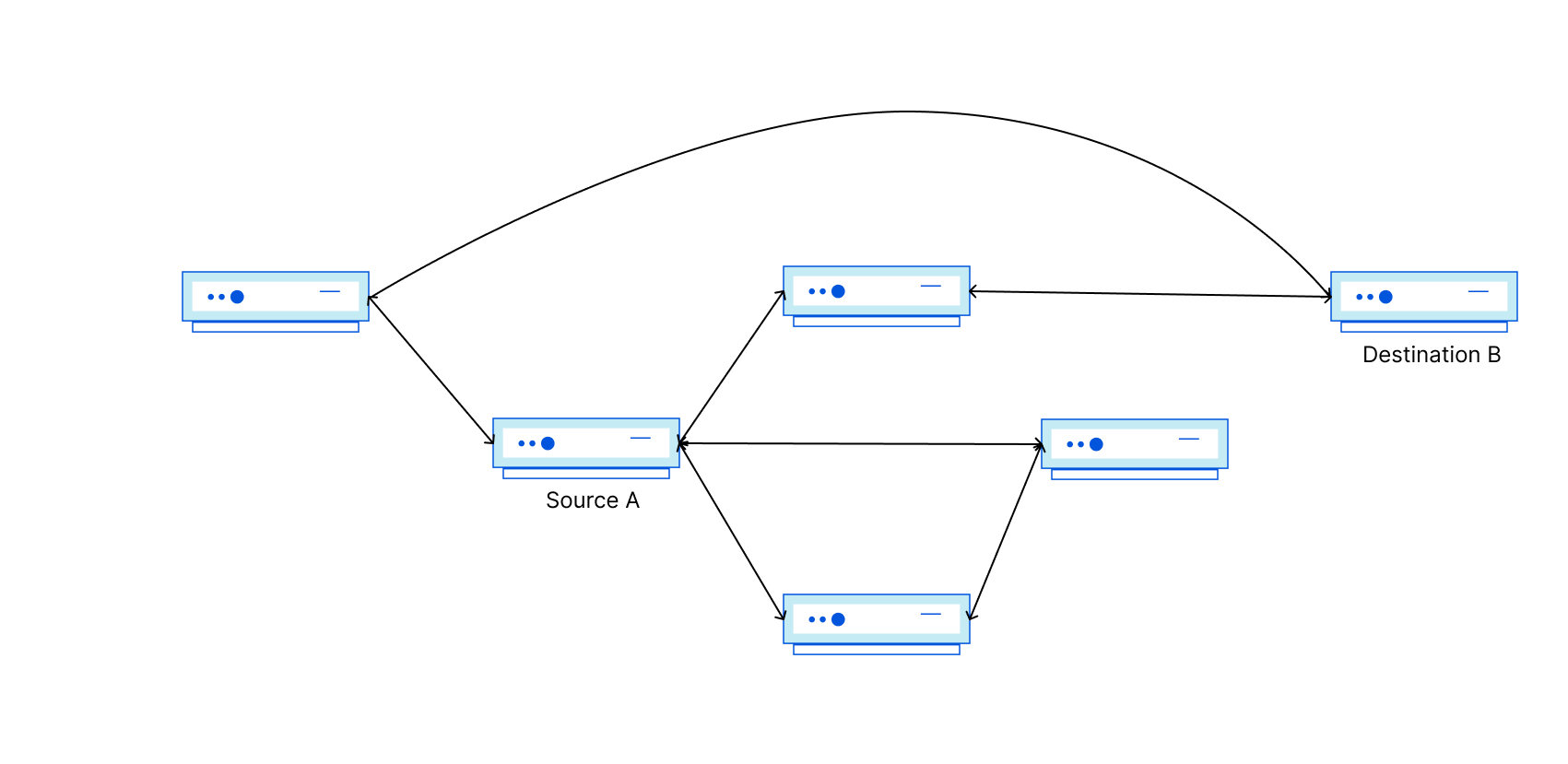

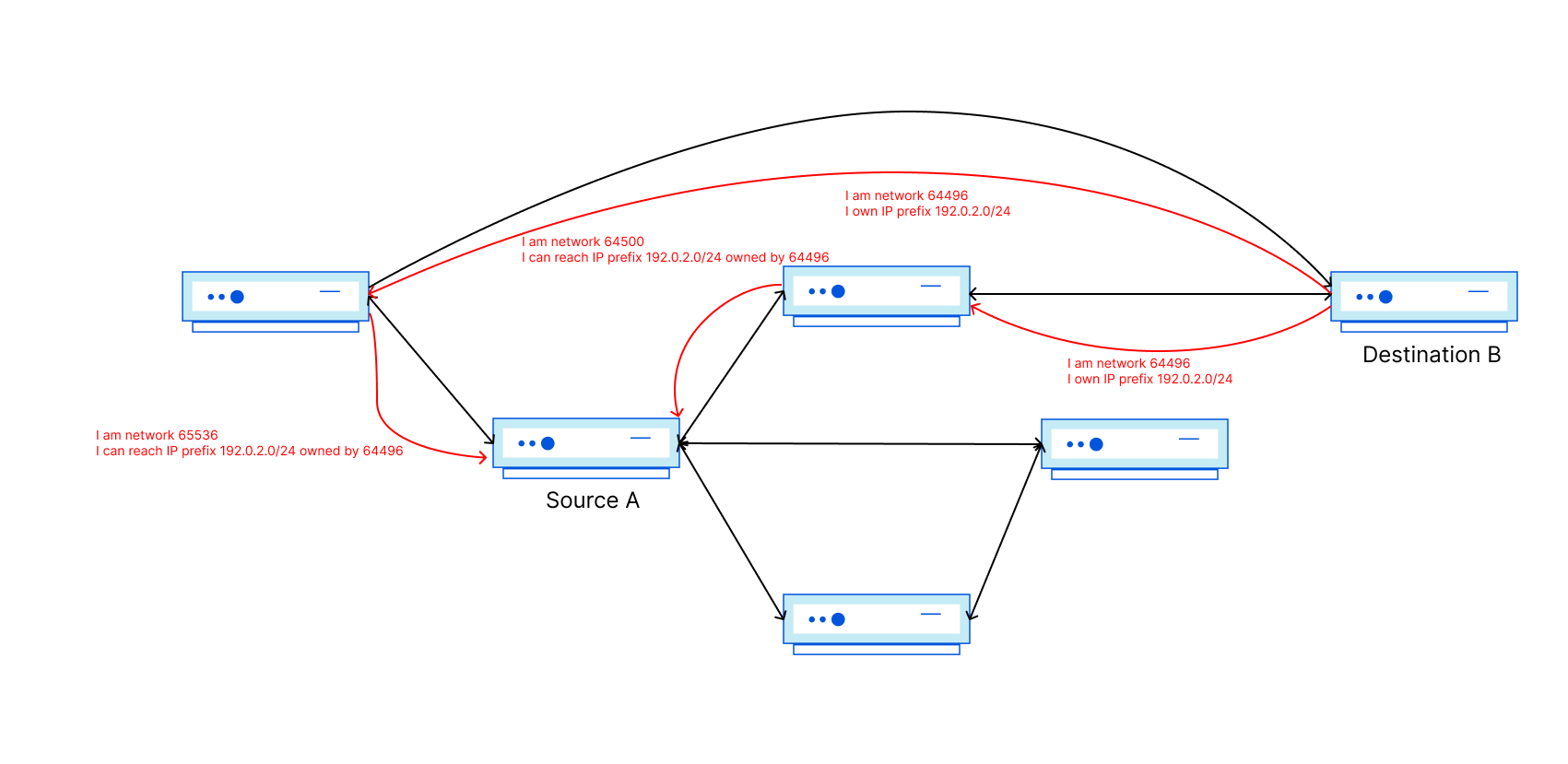

Now recall that Autonomous Systems are independently operated and controlled. In the Internet’s network of networks, how do I tell Source A in some other network that there is an available path to get to Destination B in (or through) my network? In comes BGP! BGP is the Border Gateway Protocol, and it is used to signal reachability information. Signal messages generated by the source ASN are referred to as ‘announcements’ because they declare to the Internet that IP addresses in the prefix are online and reachable.

Have a look at the figure above. Source A should now know how to get to Destination B through 2 different networks!

This is what an actual BGP message would look like:

BGP Message

Type: UPDATE Message

Path Attributes:

Path Attribute - Origin: IGP

Path Attribute - AS_PATH: 64500 64496

Path Attribute - NEXT_HOP: 198.51.100.1

Path Attribute - COMMUNITIES: 64500:13335

Path Attribute - Multi Exit Discriminator (MED): 100

Network Layer Reachability Information (NLRI):

192.0.2.0/24

As you can see, BGP messages contain more than just the IP prefix (the NLRI bit) and the path, but also a bunch of other metadata that provides additional information about the path. Other fields include communities (more on that later), as well as MED, or origin code. MED is a suggestion to other directly connected networks on which path should be taken if multiple options are available, and the lowest value wins. The origin code can be one of three values: IGP, EGP or Incomplete. IGP will be set if you originate the prefix through BGP, EGP is no longer used (it’s an ancient routing protocol), and Incomplete is set when you distribute a prefix into BGP from another routing protocol (like IS-IS or OSPF).

Now that source A knows how to get to Destination B through two different networks, let's talk about traffic engineering!

Traffic engineering

Traffic engineering is a critical part of the day to day management of any network. Just like in the physical world, detours can be put in place by operators to optimize the traffic flows into (inbound) and out of (outbound) their network. Outbound traffic engineering is significantly easier than inbound traffic engineering because operators can choose from neighboring networks, even prioritize some traffic over others. In contrast, inbound traffic engineering requires influencing a network that is operated by someone else entirely. The autonomy and self-governance of a network is paramount, so operators use available tools to inform or shape inbound packet flows from other networks. The understanding and use of those tools is complex, and can be a challenge.

The available set of traffic engineering tools, both in- and outbound, rely on manipulating attributes (metadata) of a given route. As we’re talking about traffic engineering between independent networks, we’ll be manipulating the attributes of an EBGP-learned route. BGP can be split into two categories:

- EBGP: BGP communication between two different ASNs

- IBGP: BGP communication within the same ASN.

While the protocol is the same, certain attributes can be exchanged on an IBGP session that aren’t exchanged on an EBGP session. One of those is local-preference. More on that in a moment.

BGP best path selection

When a network is connected to multiple other networks and service providers, it can receive path information to the same IP prefix from many of those networks, each with slightly different attributes. It is then up to the receiving network of that information to use a BGP best path selection algorithm to pick the “best” prefix (and route), and use this to forward IP traffic. I’ve put “best” in quotation marks, as best is a subjective requirement. “Best” is frequently the shortest, but what can be best for my network might not be the best outcome for another network.

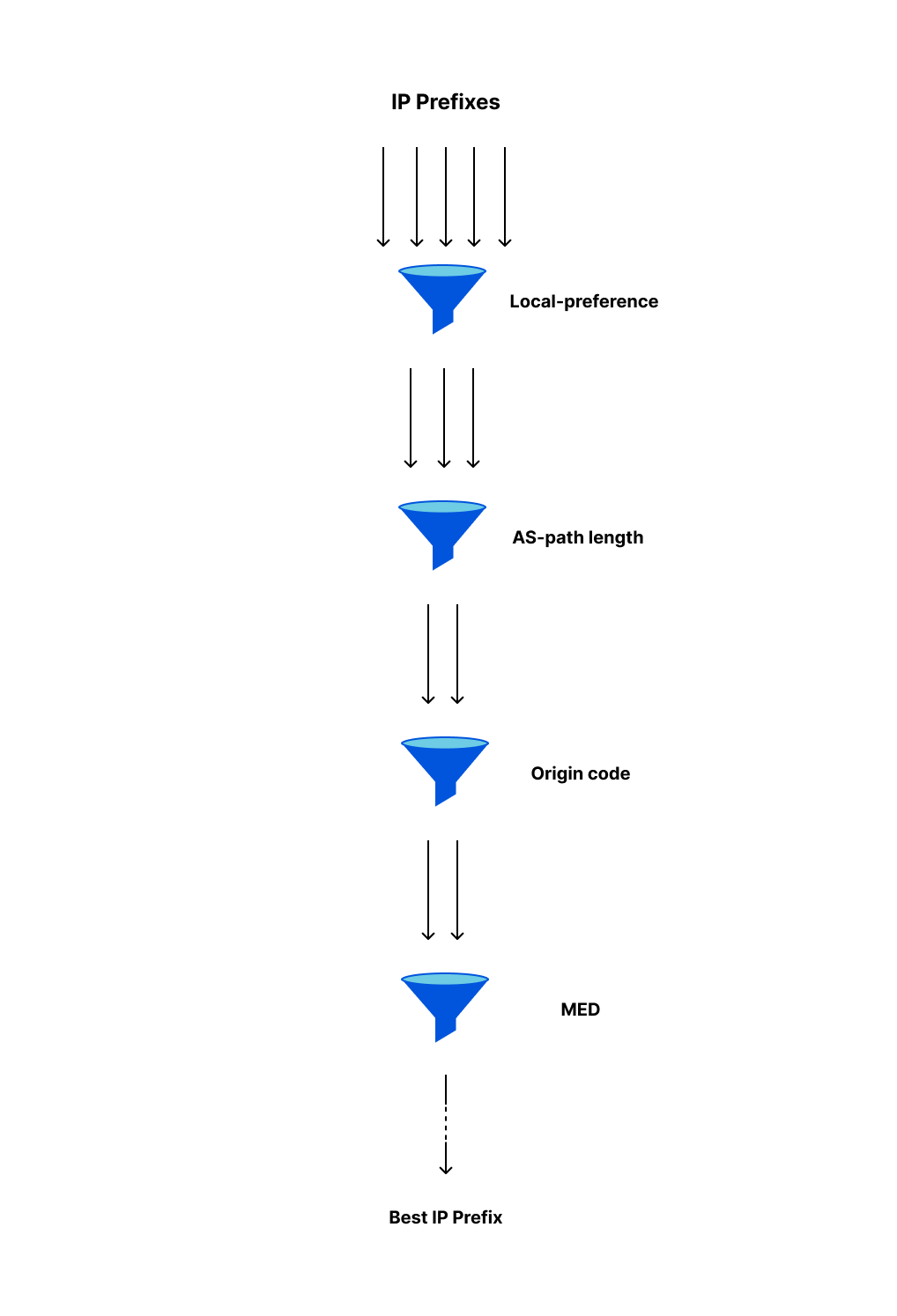

BGP will consider multiple prefix attributes when filtering through the received options. However, rather than combine all those attributes into a single selection criteria, BGP best path selection uses the attributes in tiers -- at any tier, if the available attributes are sufficient to choose the best path, then the algorithm terminates with that choice.

The BGP best path selection algorithm is extensive, containing 15 discrete steps to select the best available path for a given prefix. Given the numerous steps, it’s in the interest of the network to decide the best path as early as possible. The first four steps are most used and influential, and are depicted in the figure below as sieves.

Picking the shortest path possible is usually a good idea, which is why “AS-path length” is a step executed early on in the algorithm. However, looking at the figure above, “AS-path length” appears second, despite being the attribute to find the shortest path. So let’s talk about the first step: local preference.

Local preference

Local preference is an operator favorite because it allows them to handpick a route+path combination of their choice. It’s the first attribute in the algorithm because it is unique for any given route+neighbor+AS-path combination.

A network sets the local preference on import of a route (having learned about the route from a neighbor network). Being a non-transitive property, meaning that it’s an attribute that is never sent in an EBGP message to other networks. This intrinsically means, for example, that the operator of AS 64496 can’t set the local preference of routes to their own (or transiting) IP prefixes inside neighboring AS 64511. The inability to do so is partially why inbound traffic engineering through EBGP is so difficult.

Prepending artificially increases AS-path length

Since no network is able to directly set the local preference for a prefix inside another network, the first opportunity to influence other networks’ choices is modifying the AS-path. If the next hops are valid, and the local preference for all the different paths for a given route are the same, modifying the AS-path is an obvious option to change the path traffic will take towards your network. In a BGP message, prepending looks like this:

BEFORE:

BGP Message

Type: UPDATE Message

Path Attributes:

Path Attribute - Origin: IGP

Path Attribute - AS_PATH: 64500 64496

Path Attribute - NEXT_HOP: 198.51.100.1

Path Attribute - COMMUNITIES: 64500:13335

Path Attribute - Multi Exit Discriminator (MED): 100

Network Layer Reachability Information (NLRI):

192.0.2.0/24

AFTER:

BGP Message

Type: UPDATE Message

Path Attributes:

Path Attribute - Origin: IGP

Path Attribute - AS_PATH: 64500 64496 64496

Path Attribute - NEXT_HOP: 198.51.100.1

Path Attribute - COMMUNITIES: 64500:13335

Path Attribute - Multi Exit Discriminator (MED): 100

Network Layer Reachability Information (NLRI):

192.0.2.0/24

Specifically, operators can do AS-path prepending. When doing AS-path prepending, an operator adds additional autonomous systems to the path (usually the operator uses their own AS, but that’s not enforced in the protocol). This way, an AS-path can go from a length of 1 to a length of 255. As the length has now increased dramatically, that specific path for the route will not be chosen. By changing the AS-path advertised to different peers, an operator can control the traffic flows coming into their network.

Unfortunately, prepending has a catch: To be the deciding factor, all the other attributes need to be equal. This is rarely true, especially in large networks that are able to choose from many possible routes to a destination.

Business Policy Engine

BGP is colloquially also referred to as a Business Policy Engine: it does not select the best path from a performance point of view; instead, and more often than not, it will select the best path from a business point of view. The business criteria could be anything from investment (port) efficiency to increased revenue, and more. This may sound strange but, believe it or not, this is what BGP is designed to do! The power (and complexity) of BGP is that it enables a network operator to make choices according to the operator’s needs, contracts, and policies, many of which cannot be reflected by conventional notions of engineering performance.

Different local preferences

A lot of networks (including Cloudflare) assign a local preference depending on the type of connection used to send us the routes. A higher value is a higher preference. For example, routes learned from transit network connections will get a lower local preference of 100 because they are the most costly to use; backbone-learned routes will be 150, Internet exchange (IX) routes get 200, and lastly private interconnect (PNI) routes get 250. This means that for egress (outbound) traffic, the Cloudflare network, by default, will prefer a PNI-learned route, even if a shorter AS-path is available through an IX or transit neighbor.

Part of the reason a PNI is preferred over an IX is reliability, because there is no third-party switching platform involved that is out of our control, which is important because we operate on the assumption that all hardware can and will eventually break. Another part of the reason is for port efficiency reasons. Here, efficiency is defined by cost per megabit transferred on each port. Roughly speaking, the cost is calculated by:

((cost_of_switch / port_count) + transceiver_cost)

which is combined with the cross-connect cost (might be monthly recurring (MRC), or a one-time fee). PNI is preferable because it helps to optimize value by reducing the overall cost per megabit transferred, because the unit price decreases with higher utilization of the port.

This reasoning is similar for a lot of other networks, and is very prevalent in transit networks. BGP is at least as much about cost and business policy, as it is about performance.

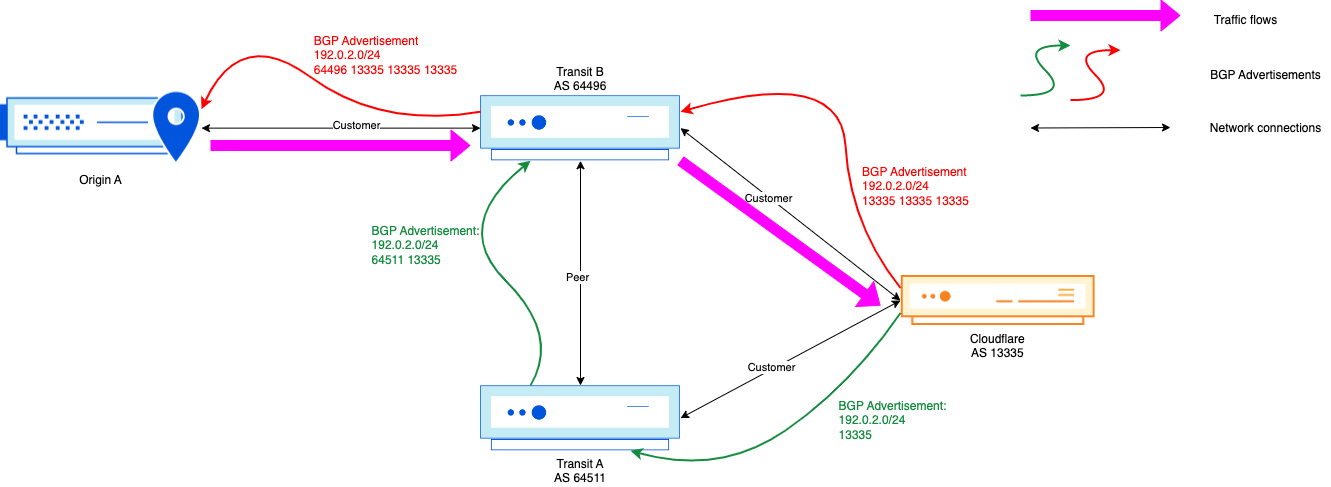

Transit local preference

For simplicity, when referring to transits, I mean the traditional tier-1 transit networks. Due to the nature of these networks, they have two distinct sets of network peers:

1. Customers (like Cloudflare)

2. Settlement-free peers (like other tier-1 networks)

In normal circumstances, transit customers will get a higher local preference assigned than the local preference used for their settlement-free peers. This means that, no matter how much you prepend a prefix, if traffic enters that transit network, traffic will always land on your interconnection with that transit network, it will not be offloaded to another peer.

A prepend can still be used if you want to switch/offload traffic from a single link with one transit if you have multiple distinguished links with them, or if the source of traffic is multihomed behind multiple transits (and they don’t have their own local preference playbook preferring one transit over another). But inbound traffic engineering traffic away from one transit port to another through AS-path prepending has significant diminishing returns: once you’re past three prepends, it’s unlikely to change much, if anything, at that point.

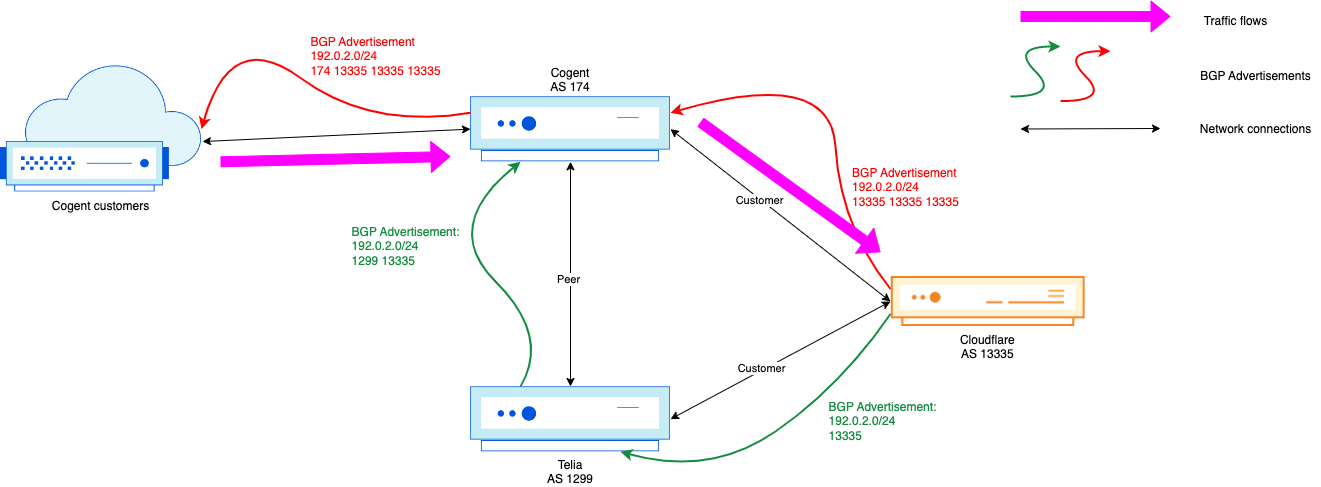

Example

In the above scenario, no matter the adjustment Cloudflare makes in its AS-path towards AS 64496, the traffic will keep flowing through the Transit B <> Cloudflare interconnection, even though the path Origin A → Transit B → Transit A → Cloudflare is shorter from an AS-path point of view.

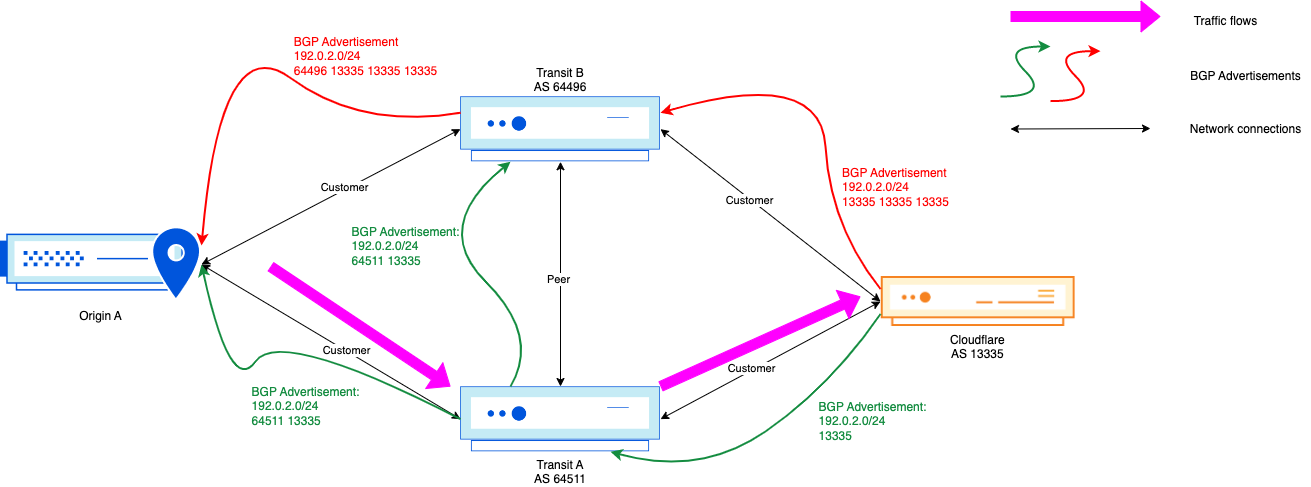

In this scenario, not a lot has changed, but Origin A is now multi-homed behind the two transit providers. In this case, the AS-path prepending was effective, as the paths seen on the Origin A side are both the prepended and non-prepended path. As long as Origin A is not doing any egress traffic engineering, and is treating both transit networks equally, then the path chosen will be Origin A → Transit A → Cloudflare.

Community-based traffic engineering

So we have now identified a pretty critical problem within the Internet ecosystem for operators: with the tools mentioned above, it’s not always (some might even say outright impossible) possible to accurately dictate paths traffic can ingress your own network, reducing the control an autonomous system has over its own network. Fortunately, there is a solution for this problem: community-based local preference.

Some transit providers allow their customers to influence the local preference in the transit network through the use of BGP communities. BGP communities are an optional transitive attribute for a route advertisement. The communities can be informative (“I learned this prefix in Rome”), but they can also be used to trigger actions on the receiving side. For example, Cogent publishes the following action communities:

| Community | Local preference |

|---|---|

| 174:10 | 10 |

| 174:70 | 70 |

| 174:120 | 120 |

| 174:125 | 125 |

| 174:135 | 135 |

| 174:140 | 140 |

When you know that Cogent uses the following default local preferences in their network:

Peers → Local preference 100

Customers → Local preference 130

It’s easy to see how we could use the communities provided to change the route used. It’s important to note though that, as we can’t set the local preference of a route to 100 (or 130), AS-path prepending remains largely irrelevant, as the local preference won’t ever be the same.

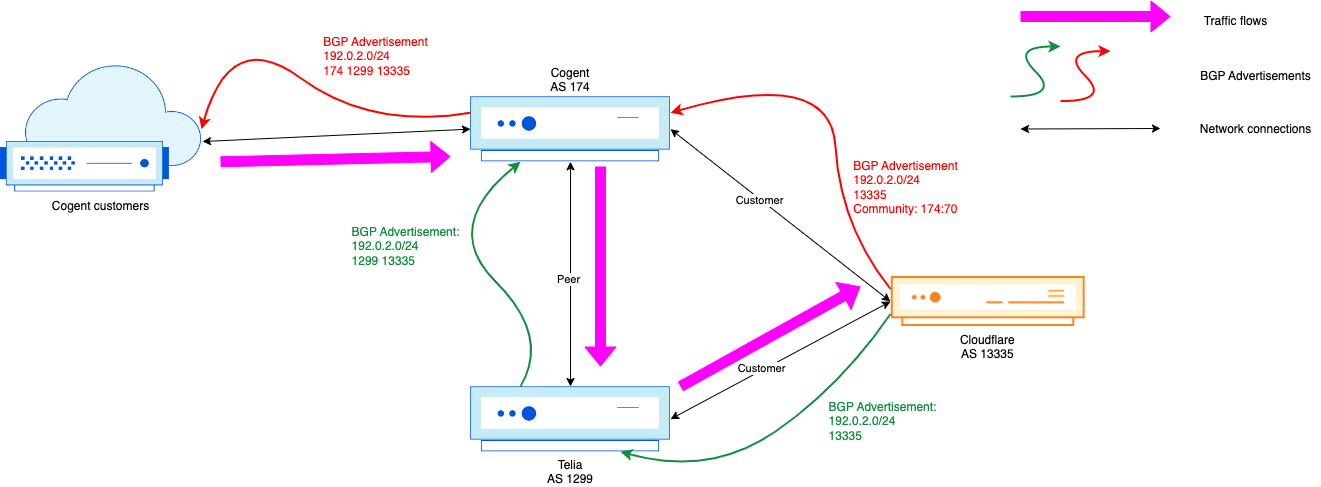

Take for example the following configuration:

term ADV-SITELOCAL {

from {

prefix-list SITE-LOCAL;

route-type internal;

}

then {

as-path-prepend "13335 13335";

accept;

}

}

We’re prepending the Cloudflare ASN two times, resulting in a total AS-path of three, yet we were still seeing a lot (too much) traffic coming in on our Cogent link. At that point, an engineer could add another prepend, but for a well-connected network as Cloudflare, if two prepends didn’t do much, or three, then four or five isn’t going to do much either. Instead, we can leverage the Cogent communities documented above to change the routing within Cogent:

term ADV-SITELOCAL {

from {

prefix-list SITE-LOCAL;

route-type internal;

}

then {

community add COGENT_LPREF70;

accept;

}

}

The above configuration changes the traffic flow to this:

Which is exactly what we wanted!

Conclusion

AS-path prepending is still useful, and has its use as part of the toolchain for operators to do traffic engineering, but should be used sparingly. Excessive prepending opens a network up to wider spread route hijacks, which should be avoided at all costs. As such, using community-based ingress traffic engineering is highly preferred (and recommended). In cases where communities aren’t available (or not available to steer customer traffic), prepends can be applied, but I encourage operators to actively monitor their effects, and roll them back if ineffective.

As a side-note, P Marcos et al. have published an interesting paper on AS-path prepending, and go into some trends seen in relation to prepending, I highly recommend giving it a read: https://www.caida.org/catalog/papers/2020_aspath_prepending/aspath_prepending.pdf