Encrypting the web is not an easy task. Various complexities prevent websites from migrating from HTTP to HTTPS, including mixed content, which can prevent sites from functioning with HTTPS.

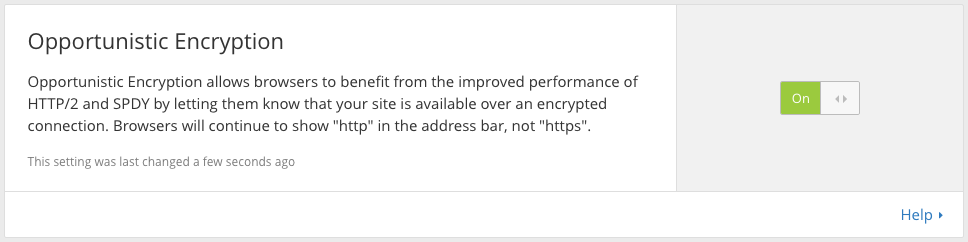

Opportunistic Encryption provides an additional level of security to websites that have not yet moved to HTTPS and the performance benefits of HTTP/2. Users will not see a security indicator for HTTPS in the address bar when visiting a site using Opportunistic Encryption, but the connection from the browser to the server is encrypted.

In December 2015, CloudFlare introduced HTTP/2, the latest version of HTTP, that can result in improved performance for websites. HTTP/2 can’t be used without encryption, and before now, that meant HTTPS. Opportunistic Encryption, based on an IETF draft, enables servers to accept HTTP requests over an encrypted connection, allowing HTTP/2 connections for non-HTTPS sites. This is a first.

Combined with TLS 1.3 and HTTP/2 Server Push, Opportunistic Encryption can result in significant performance gains, while also providing security benefits.

Opportunistic Encryption is now available to all CloudFlare customers, enabled by default for Free and Pro plans. The option is available in the Crypto tab of the CloudFlare dashboard:

How it works

Opportunistic Encryption uses HTTP Alternative Services, a mechanism that allows servers to tell clients that the service they are accessing is available at another network location or over another protocol. When a supporting browser makes a request to a CloudFlare site with Opportunistic Encryption enabled, CloudFlare adds an Alternative Service header to indicate that the site is available over HTTP/2 (or SPDY) on port 443.

For customers with HTTP/2 enabled:

Alt-Svc: h2=”:443”; ma=60

For customers with HTTP/2 disabled:

Alt-Svc: spdy/3.1=”:443”; ma=60

This header simply states that the domain can be authoritatively accessed using HTTP/2 (“h2”) or SPDY 3.1 (“spdy/3.1”) at the same network address, over port 443 (the standard HTTPS port). The field “ma” (max-age) indicates how long in seconds the client should remember the existence of the alternative service.

CC BY-SA 2.0 image by Evan Jackson

When Firefox (or any other browser that supports Opportunistic Encryption) receives an “h2” Alt-Svc header, it knows that the site is available using HTTP/2 over TLS on port 443. For any subsequent HTTP requests to that domain, the browser will connect using TLS on port 443, where the server will present a certificate for the domain signed by a trusted certificate authority. The browser will then validate the certificate. If the connection succeeds, the browser will send the requests over that connection using HTTP/2.

Opportunistically encrypted requests will contain “http” in the :scheme pseudo-header instead of “https”. From a bit-on-the-wire perspective, this pseudo-header is the only difference between HTTP requests with Opportunistic Encryption over TLS and HTTPS. However, there is a big difference between how browsers treat assets fetched using HTTP vs. HTTPS URLs (as discussed below).

HTTP Alternative Services is a relatively new but widely used mechanism. For example, Alt-Svc is used by Google to advertise support for their experimental transport protocol, QUIC, to browsers in much the same way as we use it to advertise support for Opportunistic Encryption.

Why not just use HTTPS?

CloudFlare enables HTTPS by default for customers on all plans using Universal SSL. However, some sites choose to continue to allow access to their sites via unencrypted HTTP. The main reason for this is mixed content. If a site contains references to HTTP images, or makes requests to HTTP URLs via embedded scripts, browsers will present warnings or even block requests outright, often breaking the functionality of the site.

CC BY 2.0 image by Blondinrikard Fröberg

Making sure a site can be fully migrated to HTTPS can be a manual and time-consuming process. It can require someone to manually inspect every page on a site or set up a Content Security Policy (CSP) reporting infrastructure, a complex task. Even after all this work, fixing mixed content issues may require changes in middleware or content management software that can’t be easily updated. Later this week, we’ll introduce Automatic HTTPS Rewrites, which helps fix mixed content for many sites, but not all. Some mixed content can’t be fixed because the included third party resources (such as ads) that are not available over HTTPS. Websites that can’t update fully to HTTPS will benefit most from Opportunistic Encryption.

With Opportunistic Encryption, supporting browsers can choose to access an HTTP site using HTTP/2 over an encrypted connection instead of HTTP/1.1 over plaintext (the default).

Security Benefits

It’s no secret that network operators have access to the data that travels through their equipment. This access can be used to modify data: ISPs have been caught injecting unwanted data (such as advertisements and tracking cookies) into unencrypted requests. Countries routinely filter content by inspecting HTTP headers in unencrypted traffic, and China’s Great Cannon injected malicious code into unencrypted websites. Access to data in transit can also be used to perform dragnet surveillance, where vast swaths of data is collected and then shipped to a central location for analysis.

Opportunistic Encryption does not fully protect against attackers who can simply remove the header that signals support for Opportunistic Encryption to the browser. However, once an opportunistically encrypted connection is established all requests sent over the connection are encrypted and cannot be read (or modified) by prying eyes.

Terminology is hard

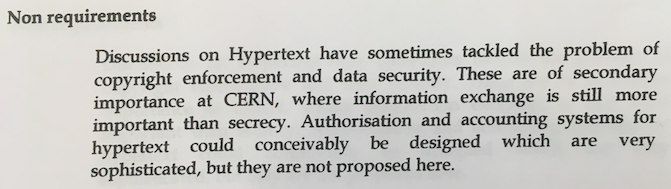

Tim Berners-Lee initiated the development of HTTP in the late 1980s to facilitate the transfer of documents from servers to clients. Both websites and browsers were rudimentary compared to the today’s web ecosystem. The concept of web security was practically non-existent.

From the original 1989 paper:

As the use cases of the web expanded to include sensitive data transactions, some security was needed. Multiple encryption schemes were developed to help secure HTTP, including S-HTTP and the eventual winner, HTTPS.

Originally, the difference between HTTP and HTTPS was one of layering. In HTTP, messages were written to the network directly, and in HTTPS, a secure connection was established between the client and server using SSL (an encryption and authentication protocol), and standard HTTP messages were written to the encrypted connection. Browsers signaled HTTP websites with an open lock icon, whereas HTTPS websites received a closed lock. Later, SSL evolved into TLS, although people sometimes still refer to it as SSL.

As websites became much more complex, embedded scripts and dynamic content became commonplace. Serving insecure content on a secure web page was identified as a risk and HTTPS started to take on a more nuanced meaning. Rather than just HTTP on an encrypted connection, HTTPS meant secure HTTP. For example, cookies became a popular way to store state in the client for managing web sessions. Cookies obtained over a secure connection were not allowed to be sent over insecure HTTP or modified by data obtained over HTTP. New privacy-sensitive features now require HTTPS (such as the Location API). This distinction between HTTP and HTTPS has been further codified by the W3C, the standards body in charge of the web, in their Secure Contexts document.

To break it down:

- HTTP is a protocol for transferring hypertext

- TLS/SSL is a protocol for encrypted communication

- HTTPS is a protocol for transferring secure hypertext

| HTTP | HTTPS | |

|---|---|---|

| Unencrypted | ✔️ | ❌ |

| Encrypted with TLS | ✔️ | ✔️ |

Opportunistic Encryption is the bottom left ✔️. While only HTTPS sites are treated as secure by the browser (as indicated by a green lock security indicator), encrypted HTTP is preferable to unencrypted HTTP.

Browser support

All versions of Firefox since Firefox 38 (May 2015) have supported Opportunistic Encryption in its original form (without certificate validation). Firefox has recently added support for certificate validation in Firefox Nightly and will support it in an upcoming official release. We believe that Opportunistic Encryption is a meaningful advance in web security. We hope that other browsers follow Firefox’s lead and enable Opportunistic Encryption.

To be clear, Opportunistic Encryption is not a replacement for HTTPS. HTTPS should always be used when both strong encryption and authentication are required. For sites that don’t have the resources to fully move to HTTPS, Opportunistic Encryption can help, providing both added security and performance. Every bit counts.